The Green Rent: How Realigning Our Tax System Can Rewild the Planet

We live in an age of profound paradox. Despite generating unprecedented technological and material progress, our societies are fractured by deepening inequality and face the cascading consequences of catastrophic ecological decline. We are told these crises are impossibly complex, but what if they are not separate issues? What if they are symptoms of a single, hidden defect in our economic system: the private capture of communally created wealth from land and nature? The thesis of this report is that to heal our planet, we do not need more complex regulations or futile trade-offs between the economy and the environment. The solution lies in a simple yet radical realignment of our tax system—a shift that can curb destructive speculation, restore social equity, save wildlife, and ultimately, rewild the planet.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. The Tragedy of the Privates: Why Our Economy Destroys Nature

To solve the environmental crisis, we must first correctly diagnose its economic drivers. The familiar concept of the “tragedy of the commons” has long been misapplied. The true crisis, as conservationist Peter Smith argues, is a “tragedy of the privates,” where the private exploitation of common resources for profit has become the primary engine of ecological destruction. This system has incentivised a relentless assault on the natural world, fueling everything from biodiversity loss to climate change. To reverse this damage, we must understand that this is not a passive failure; it is a system actively engineered to destroy nature. Reversing its logic is the key to liberating land for nature’s recovery.

The Economic Drivers of Ecological Collapse

Our current economic model actively promotes environmental harm by systematically severing the connections that sustain life. This destruction manifests in three critical ways:

1. Spatial Fragmentation: We have carved up natural landscapes into isolated islands, preventing the movement of wildlife and disrupting the gene flow essential for healthy populations.

2. Trophic Disintegration: The complex web of life—from the mycorrhizal fungi in the soil to apex predators—is being torn apart. This collapse of the “trophic cascade” undermines the fundamental processes of nutrient cycling and soil formation.

3. Collapse in Bioabundance: The most alarming consequence is not just the loss of species, but the staggering decline in the sheer quantity of individual organisms. The dramatic drop in insect and bird populations across the UK is a stark indicator of this systemic decay.

The Insurmountable Barriers to Conservation

Within this economic framework, traditional conservation efforts face insurmountable obstacles. The most fundamental barrier to rewilding and habitat restoration is the prohibitive cost of land—a direct result of the private capture of land’s unearned rental value. Driven by rampant speculation, land prices have skyrocketed. As Peter Smith notes, they have increased “40-fold since I began my career.” This speculative fever, untethered from the land’s productive use, makes it nearly impossible for conservation trusts or communities to acquire land on a scale that could make a meaningful ecological difference, effectively locking nature out of the market.

Perverse Incentives in the Tax Code

Worse still, the current tax system—a key tool of the parasitic “Predator culture”—creates perverse incentives that actively penalise landowners for choosing conservation. Inheritance tax reliefs are a powerful driver of this destructive behaviour.

* Agricultural Property Relief (APR) provides a significant tax break, but only for land actively used for agricultural purposes. A landowner who decides to rewild a field could lose this valuable relief, creating a direct financial disincentive to restore habitats.

* Business Property Relief (BPR) may be available for activities like eco-tourism, but not for simply letting land be wild, as the venture must be a trading enterprise carried on for gain.

These policies lock in ecologically harmful practices by making them the most financially rational choice. To reverse this damage, we must look beyond the symptoms and address the underlying economic disease.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2. Unearthing the Root Cause: The Privatisation of Economic Rent

To understand why our economy incentivises destruction, we must first grasp the concept of “economic rent.” This is not the payment for a flat, but the hidden surplus that, when privatised, distorts our entire economic system. This is the prize in the battle between those who produce wealth and those who extract it. By deconstructing this core concept, we can reveal the foundational flaw—the hidden defect—in our economic architecture.

Economic Rent vs. Wages and Profit

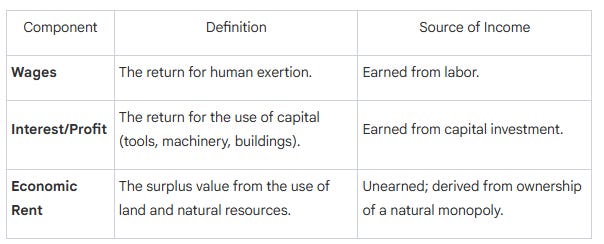

In economics, all returns flow from three sources: labor, capital, and land. Understanding their distinct nature is critical.

Economic rent is the unearned income derived from the exclusive control of land. It is the surplus that remains after both labour (wages) and capital (profit) have been paid for their contributions. As Adam Smith noted, landlords are unique in that their revenue “costs them neither labour nor care, but comes to them, as it were, of its own accord.”

The Community’s Role in Value Creation

Crucially, economic rent is not created by the individual landowner. It is created by the presence and activities of the community as a whole. A parcel of desert land has no rent, but the same parcel in the centre of a thriving city commands an enormous rent—not because of anything the owner did, but because of the community built around it. This value is generated by taxpayer-funded public investments and social amenities. A new railway line causes nearby land values to soar. The presence of good schools can add thousands of pounds to the price of a home. This publicly created value is “allowed to cascade down into the land market, where it was then pocketed by land owners.” Economic rent is, therefore, the publicly created value that is privately captured.

The “Predator vs. Producer” Dynamic

This private capture of rent creates a fundamental conflict between two opposing cultures within capitalism:

1. The Producer Culture: Comprised of those who create societal wealth through their labour and capital.

2. The Predator Culture: A parasitic group that seeks not to create wealth, but to extract it by monopolising land and capturing its communally-created rent.

This dynamic is a primary cause of systemic inequality. As society progresses, the producers, workers and businesses are forced to pay an ever-increasing portion of their earnings to the predators for the mere right to live and work.

The Economic Consequences of Privatised Rent

The private capture of rent does more than create inequality; it is the engine of the predictable 18-year cycle of economic booms and busts—a recurring symptom of the hidden defect in our economic code. The cycle works as follows:

1. Boom: As the economy grows, demand for land increases, and its rental value rises.

2. Speculative Fever: Rising land values make it more profitable to speculate on land than to invest in productive businesses. Money floods the real estate market, driving prices to unsustainable levels.

3. Strangulation: These speculative land prices act as a private tax on the productive economy, choking off investment, suppressing wages, and making housing unaffordable.

4. Crash: The bubble inevitably bursts. Land values collapse, triggering a major depression and widespread unemployment.

This cycle ensures that the gains from progress are intercepted by a select few, while the productive economy is periodically driven into crisis. The privatisation of our common wealth demands a new source of public revenue that restores balance instead of disrupting it.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3. A Three-Pronged Solution: The Geoist Tax Revolution

The Geoist framework offers a comprehensive and elegant solution. This approach fundamentally shifts the tax burden away from the Producer culture—labour and investment—and onto the unearned income derived from our common resources. It is the mechanism that re-empowers producers and aligns economic incentives with ecological health.

3.1. Land Value Tax (LVT): Rewriting the Rules of Land Use

A Land Value Tax (LVT) is an annual tax levied not on the total value of a property, but specifically on the unimproved rental value of the land itself. This means that buildings, crops, and other improvements are not taxed; the levy captures only the value that is created by nature and the surrounding community—from public infrastructure to social amenities. This simple change has a cascade of profoundly positive effects.

* Curbing Speculation: By requiring landowners to pay an annual levy on the rental value of their sites, LVT makes it unprofitable to hold land vacant or under-utilised purely for speculative gain. This would crash the speculative bubble in land prices, making land affordable again.

* Promoting Efficient Land Use: LVT incentivises landowners to put their sites to the best possible use. This encourages the development of derelict brownfield sites within cities, leading to more compact, resource-efficient urban areas.

* Protecting Green Belts: As LVT makes it more economical to develop existing urban sites, the pressure to build on green belts and open spaces is significantly reduced.

* Shifting the Margin of Production: As Peter Smith notes, a crucial ecological benefit of LVT is that it would change the economic calculus for marginal land. Land that is not commercially viable for farming or development—land “below the margin of production”—would no longer be held for speculation. It would effectively be abandoned by commercial interests, allowing it to rewild naturally. This directly reverses the “tragedy of the privates,” making land abandonment for ecological recovery the most logical economic outcome for non-viable sites.

3.2. Resource and Pollution Taxes: Paying the True Cost

Complementing LVT are taxes designed to make producers and consumers pay the true social and environmental cost of resource use and pollution.

* Natural Resource Taxes: These include severance taxes on the extraction of finite resources like oil and timber, and abstraction charges on resources like water. This ensures that the public is compensated for the private use of shared natural wealth.

* Pollution Taxes (Pigouvian Taxes): A Carbon Tax is the primary example. By placing a direct tax on carbon at its source (e.g., the oil well or coal mine), the environmental cost is “internalised” into the price of goods and services.

As demonstrated by successful UK policies, these taxes powerfully harness entrepreneurial drive. The plastic bag tax led to a 98% reduction in use, while the landfill tax achieved a 90% reduction in waste. This approach unleashes a wave of innovation as businesses are driven to find more resource-efficient and less polluting ways of operating. This suite of taxes provides the economic mechanism to drive tangible, real-world ecological restoration.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4. From Perverse Incentives to Planetary Prosperity: The Ecological Payoff

By correcting the foundational economic flaw described earlier, these tax reforms can unleash the power of nature to heal itself, creating a world where ecological restoration becomes the most logical and profitable path.

4.1. Unleashing Rewilding Through Economic Liberation

A Land Value Tax is the single most powerful tool for enabling large-scale rewilding. By crashing speculative land prices, it would make vast tracts of land affordable for the first time in generations. Conservation trusts, community groups, and individuals could acquire land for restoration, connecting fragmented habitats and creating core wild areas.

Into these newly liberated landscapes, we can reintroduce keystone species like the beaver. This “ecosystem engineer” creates a cascade of benefits wherever it returns:

* Its dams create complex wetlands that stop floods downstream.

* These wetlands purify water by trapping pollutants.

* They create deep, peaty soils, sequestering vast amounts of carbon.

* They foster immense biodiversity.

Modelling suggests that reintroducing beavers to just 30% of UK waterways could sequester an amount of carbon annually that is equivalent to the UK’s entire yearly human-caused emissions, representing a colossal natural climate solution. LVT makes this vision possible by breaking the speculative lock on the land.

4.2. Quantifying the Carbon Dividend of Rewilded Land

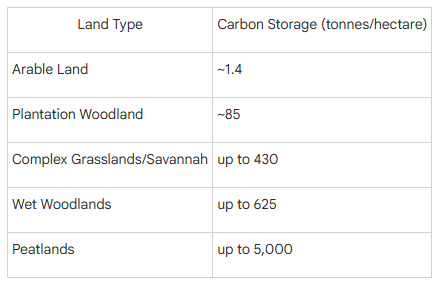

The carbon sequestration potential of restored natural habitats is colossal and tragically overlooked. As detailed in “The Rewilding Revolution,” rewilded ecosystems—particularly wetlands—are far more powerful carbon sinks than simple tree plantations.

These figures reveal that our current land use is often the least effective at storing carbon. By shifting land from low-carbon uses like intensive agriculture to high-carbon habitats like wet woodlands and peatlands, we can pull enormous quantities of CO2 from the atmosphere.

4.3. Aligning Profit with Preservation

This new tax system fundamentally rebalances our economy, turning “every capitalist into a capitalist for saving the world.” When land speculation is eliminated, and the true costs of resource extraction and pollution are priced in, the entire incentive structure is flipped on its head. It becomes more profitable to innovate and conserve resources than to waste them. It becomes more economically rational to restore ecosystems than to degrade them. The futile tradeoffs between the economy and the environment disappear, replaced by a virtuous cycle where a healthy economy depends entirely on a healthy planet.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5. Designing a Just and Green Future

Implementing such a radical shift requires nuanced policy design to maximise benefits and ensure a just transition for all members of society. A well-designed system is not only ecologically effective but also profoundly equitable.

5.1. Fine-Tuning the Mechanism: The “Green” Tax Framework

The basic Geoist framework can be refined with specific mechanisms to accelerate environmental goals.

1. A “Green” Property Tax: This is not a discount on the LVT itself, but a feature of a “split-rate” property tax system that taxes land and buildings separately. A discount would be applied to the building’s portion of the tax based on its energy efficiency, directly rewarding investment in green technologies.

2. A “Biodiversity Tax” Credit: This serves as the direct antidote to current perverse incentives. Where policies like Agricultural Property Relief currently penalise rewilding, a biodiversity tax credit would create a powerful positive incentive, rewarding landowners for acting as stewards of the commons. This credit would reduce a landowner’s LVT burden in proportion to how close their land is to its maximum native biodiversity, making private stewardship and rewilding a financially rational choice.

5.2. Ensuring a Just Transition for All

A common concern raised about LVT is its potential impact on cash-poor but land-rich households, such as pensioners. This is a legitimate concern with a straightforward solution: the right to defer.

* The Right to Defer: Homeowners would have the right to defer payment of the LVT. Upon deferral, the tax authority would register a proportionate claim against the property to be settled upon its transfer or sale. This ensures no one is forced out of their home while still allowing the community to reclaim its value.

It is crucial to recognise that the overall shift is deeply progressive. By replacing regressive taxes on the Producer culture—like income tax on workers and VAT on consumption—with taxes on the unearned wealth from land, the financial burden on ordinary people is significantly reduced. This shift directly tackles inequality, increases the prosperity of workers and small businesses, and creates a fairer society for all. A well-designed Geoist system is the foundation for a future that is both ecologically resilient and socially just.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Conclusion: The Solution Under Our Feet

Our most painful economic, social, and ecological crises are not disconnected misfortunes. They stem from a single, foundational mistake—a hidden defect in our economic code: allowing the wealth created by our communities and the natural world to be privately captured for unearned profit. The consequences are all around us—in the cycles of boom and bust, the widening gulf between rich and poor, and the relentless degradation of the biosphere that sustains us all.

The solution, therefore, is not another layer of complex bureaucracy. It is a restoration of natural balance. The shift to a system of Land Value Taxation, complemented by taxes on pollution and resource extraction, is not a burden. It is a liberation. It frees labour and capital from punitive taxation, unleashing productive enterprise. It frees our landscapes from the grip of destructive speculation, unleashing the power of the wild world to heal itself. This leaves us with a profound question: what could we achieve, as a society and as a species, if we finally recognised that the key to healing our world has been right here, under our feet, the entire time?

Comments

Post a Comment