Churchill’s Lost Radicalism: The Fight for Two Democracies

A Review of Churchill and the Two Variants of Democracy

Fred Harrison | Clifford W. Cobb

American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 2026; 0:1–7 1

https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.70026

To the modern observer, Winston Churchill is the bulldog of British conservatism, the wartime leader who defended the Empire. Yet, buried beneath this legacy lies a forgotten chapter: Churchill the Radical. In the early 20th century, Churchill was Britain’s most articulate champion of “Georgism”—the economic philosophy that land monopoly was the root of social injustice.

Drawing on the analysis by Fred Harrison and Clifford W. Cobb, as well as Churchill’s own speeches from his “radical decade,” this article reconstructs the battle between two variants of democracy: an “authentic” democracy grounded in economic rights, and the “performative” democracy that ultimately prevailed.1. The Radical Vision: “The Mother of All Monopolies”

Between 1904 and 1914, Churchill was a leading figure in the Liberal Party, deeply influenced by the American economist Henry George and his seminal work, Progress and Poverty. Churchill did not view poverty as an accident of the market, but as a structural defect caused by the private appropriation of “public value”—specifically, the rent derived from land.

The Georgist Argument

Churchill’s early campaigns were built on a distinct promise: to deliver “authentic democracy” by establishing the economic right of the community to share in the wealth it created. He argued that while individuals had a right to what they produced, the value of land was different. As the community grew and public services improved, land values rose independently of the landowner’s effort.

In a famous speech at the King’s Theatre in Edinburgh (17 July 1909), often cited as the definitive Georgist oration, Churchill attacked the ‘land monopoly’: “It is quite true that land monopoly is not the only monopoly which exists, but it is by far the greatest of monopolies—it is a perpetual monopoly, and it is the mother of all other forms of monopoly.”

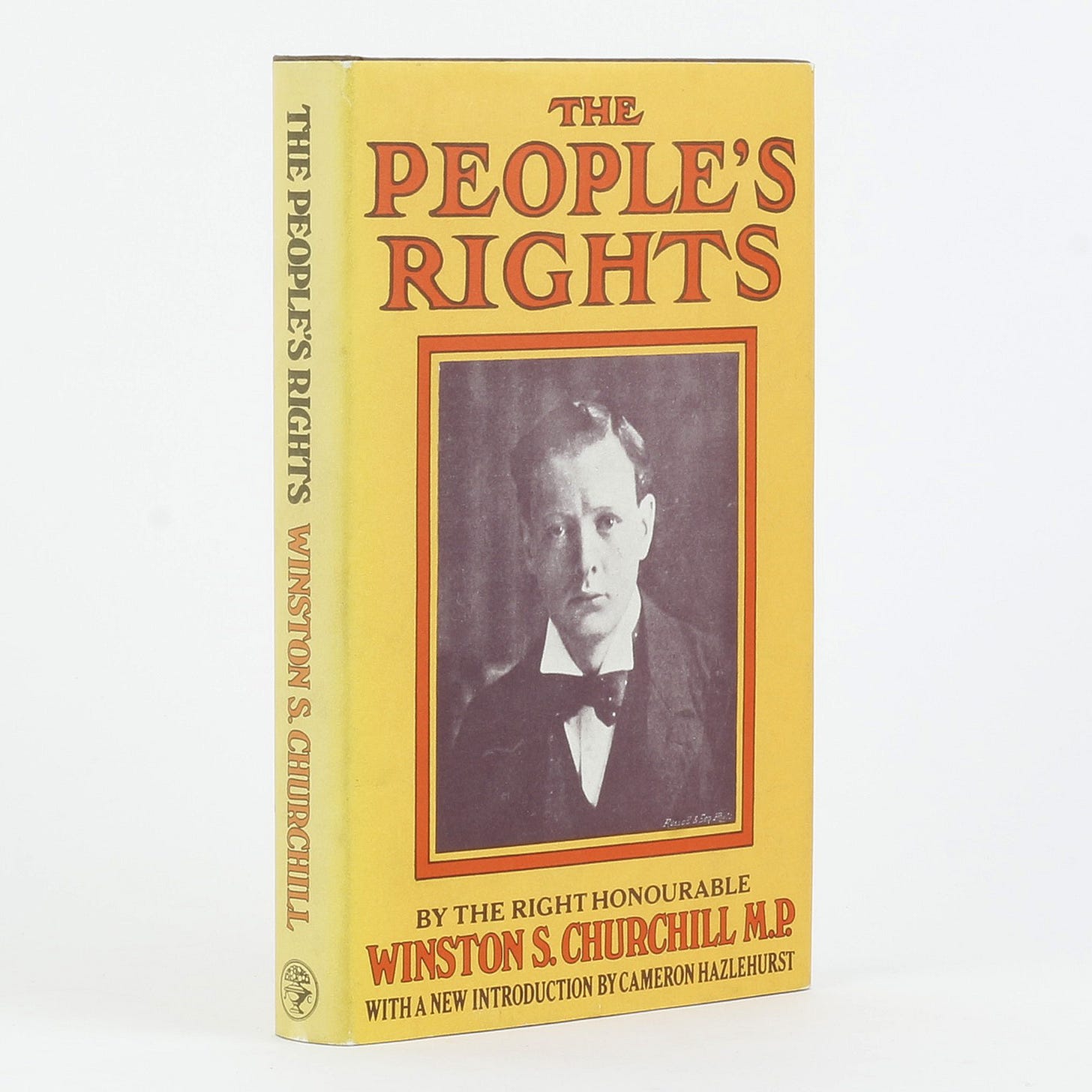

This speech, supported by his campaigning book The People’s Rights (1910), provided vivid examples of this injustice that went beyond the provided text. He famously described the “enrichment which comes to the landlord who happens to own a plot of land on the outskirts of a great city,” watching the population work and the city grow, while he “sits still” and his land value multiplies ten or twenty-fold. The Moral Distinction

Churchill was careful to distinguish between capital and land. He viewed taxes on production as an “evil”—an obstacle to trade and industry. In contrast, he argued that taxing land values was the only way to fund social reform without harming the economy:

Production vs. Plunder: Churchill believed that allowing private interests to capture community-created land value was akin to allowing “dirty fingers” to thrust into the public pie.

The Solution: A “sensible difference” in taxation where the state captures unearned income (rent) while leaving earned income (wages and profits) largely untouched.

The People’s Budget and the Constitutional Crisis

The zenith of this radicalism was the “People’s Budget” of 1909–1910. The Liberal government, driven by Churchill and Chancellor David Lloyd George, proposed a levy on land values to fund defence and social welfare.

The proposal triggered a ferocious backlash from the landed nobility, leading the House of Lords to break convention and reject the budget. This act of sabotage resulted in the Parliament Act of 1911, which stripped the Lords of their power to veto money bills, seemingly clearing the path for “authentic democracy”.

However, despite this constitutional victory, the economic victory never came. The implementation of the land tax was sabotaged from within. The valuation process was complex, and Lloyd George eventually capitulated to pressure, allowing the “landed nobility” to fend off the reform. By 1920, the taxes were repealed, and the revenue collected was returned to the taxpayers.3. The Great Betrayal: Churchill’s Switch

The tragedy of Churchill’s political career, according to Harrison and Cobb, is his transition from a radical reformer to a guardian of the status quo. After losing his seat in 1922 and rejoining the Conservative Party in 1924, Churchill became Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The 1928 Rationalisation

As Chancellor, Churchill did not attempt to educate the Conservatives on land value taxation. Instead, he succumbed to the “post-classical” economic view that treated all wealth as identical, regardless of its source. In a 1928 speech, he attempted to rationalise his abandonment of Georgism:

The “Complex Wealth” Argument: He claimed that while Henry George might have been right for a simpler time, the modern world had “hundreds of different ways of creating and possessing wealth” unrelated to land.

The Shift to Profits: Churchill argued that “radical democracy” had turned away from distinguishing sources of wealth and instead favoured the “graduated taxation of the profits of wealth” (income tax).

This marked the death of the “single tax” ideal in British politics. Churchill had accepted a system where the “idle rich” (free riders) maintained veto power over tax policy, forcing the state to tax labour and capital instead of rents.4. The Legacy: A “Performative” Democracy

The abandonment of the land value tax left Britain with a “performative politics”—a system where politicians promise to cure social ills (poverty, housing crises, unemployment) but lack the fiscal tools to address their root causes.

The Veto Power of the Free Rider

Because the state failed to capture land rents, the owners of rent-yielding assets retained a “veto power” over the public purse. This has had lasting consequences:

Infrastructure Failure: The authors note that even in 2023, attempts to tax land value uplift from public infrastructure (the “Infrastructure Levy”) were diluted or brushed aside, illustrating the continued dominance of landed interests.

Housing Crisis: The current housing affordability crisis is a direct result of the “hope value” system (codified in 1961), where the state must compensate landowners for potential future value, effectively subsidising speculation.

Fiscal Parasitism: As predicted by Adam Smith and feared by the early Churchill, the rentier class became “parasites on the body politic,” reaping wealth without “labour nor care”.

Conclusion

Winston Churchill once famously said, “Democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried.” However, the authors argue this was a rationalisation for a compromised system.

Churchill had once glimpsed a better option: an authentic democracy where the right to vote was complemented by the economic right to the national dividend (land rent). By abandoning this vision in the 1920s, Churchill helped cement a political structure where the state is funded by taxing the work of the people, rather than the wealth of the land—a decision that continues to shape economic inequality in the 21st century.

Key Historical “Georgist” Quotes from Churchill

To further illustrate his commitment during his radical phase, here are key excerpts from his speeches (1909–1910) that reinforce the provided text:

On the Passive Landlord: “Roads are made, streets are made, railway services are improved, electric light turns night into day, water is brought from reservoirs a hundred miles off in the mountains—and all the while the landlord sits still. Every one of those improvements is effected by the labour and cost of other people and the taxpayers.” (Edinburgh, 1909)

On the Evil of Land Monopoly: “Land, which is a necessity of human existence, which is the original source of all wealth, which is strictly limited in extent... differs from all other forms of property.” (The People’s Rights, 1910)

On Taxing Industry vs. Land: “We do not want to punish the landlord. We want to alter the law... It is not the man who is blameworthy for doing what the law allows... it is the State which would be blameworthy were it not to endeavour to reform the law.”

Comments

Post a Comment