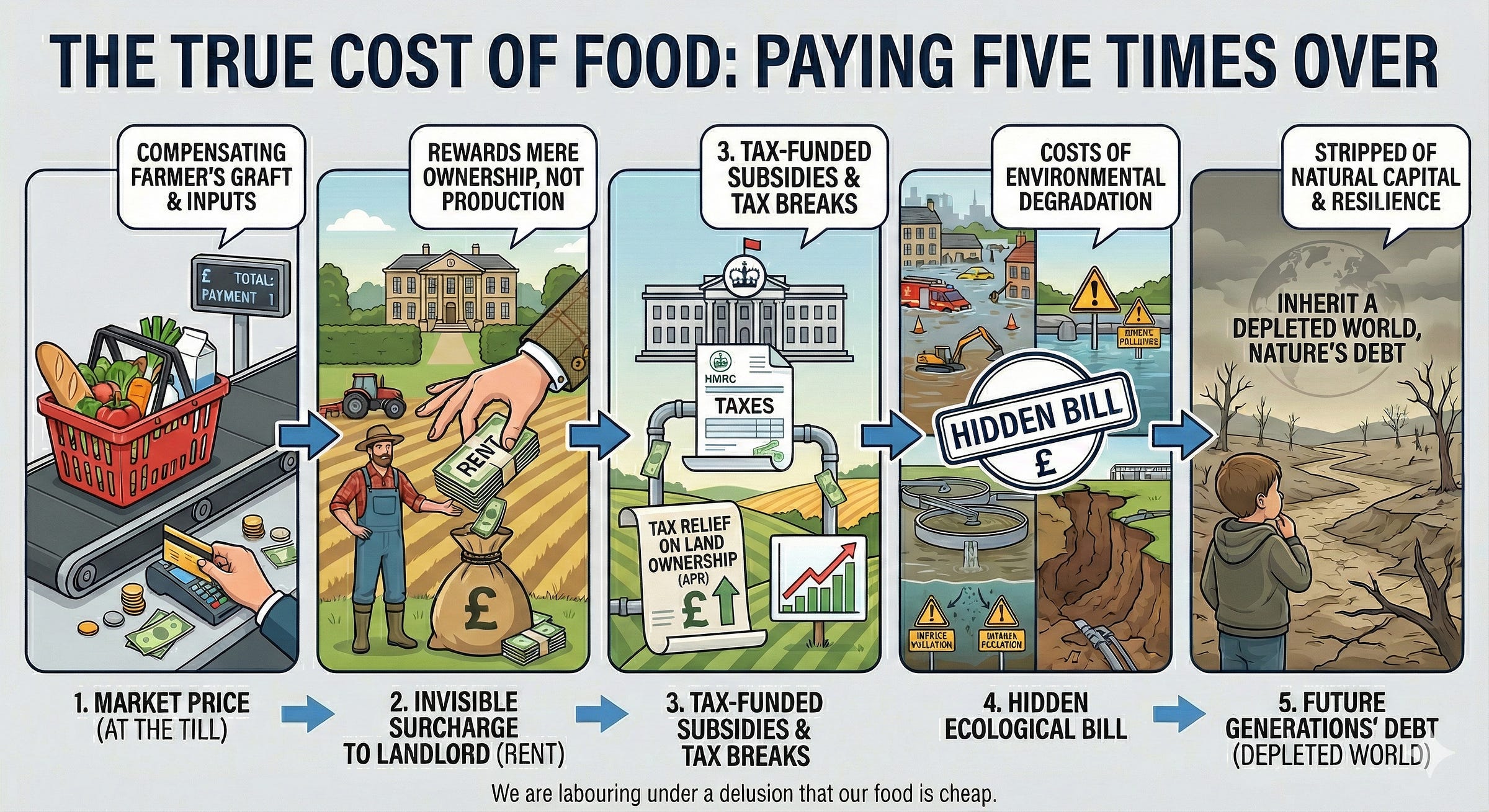

Why We Pay Five Times Over For Food

We are labouring under a delusion that our food is cheap when, in reality, we pay for it five times over. First, we pay the Cost of Production, compensating the farmer for their hard graft and inputs. Second, we pay an invisible surcharge to the landlord, as a significant portion of the farmer's revenue is siphoned off as rent, money that rewards mere ownership rather than production. Third, we pay through our taxes, funding subsidies that often prop up inefficient practices and inflate land values further. Fourth, we pay a hidden bill for ecological destruction; we cover the costs of protecting flooded towns, purifying nitrate-polluted water, and repairing infrastructure damaged by soil erosion, all consequences of forcing the land beyond its natural capacity. Finally, and most tragically, our children pay the fifth price: they inherit a depleted world, stripped of its natural capital, biodiversity, and climate resilience—a debt of nature that no amount of money can ever repay.

Let us delve into the reasons behind our current agricultural system and examine how we can transition towards a model where we only pay once for our food, ultimately leading to a system where we pay a fair price for quality food, without hidden costs or ongoing financial burdens. Transitioning to such a model not only benefits our wallets but also fosters a stronger connection between producers and consumers, promoting local economies and sustainable agricultural practices.

The Impact of Ricardo’s Law of Rent on Agricultural Practices and Biodiversity in the UK

Introduction

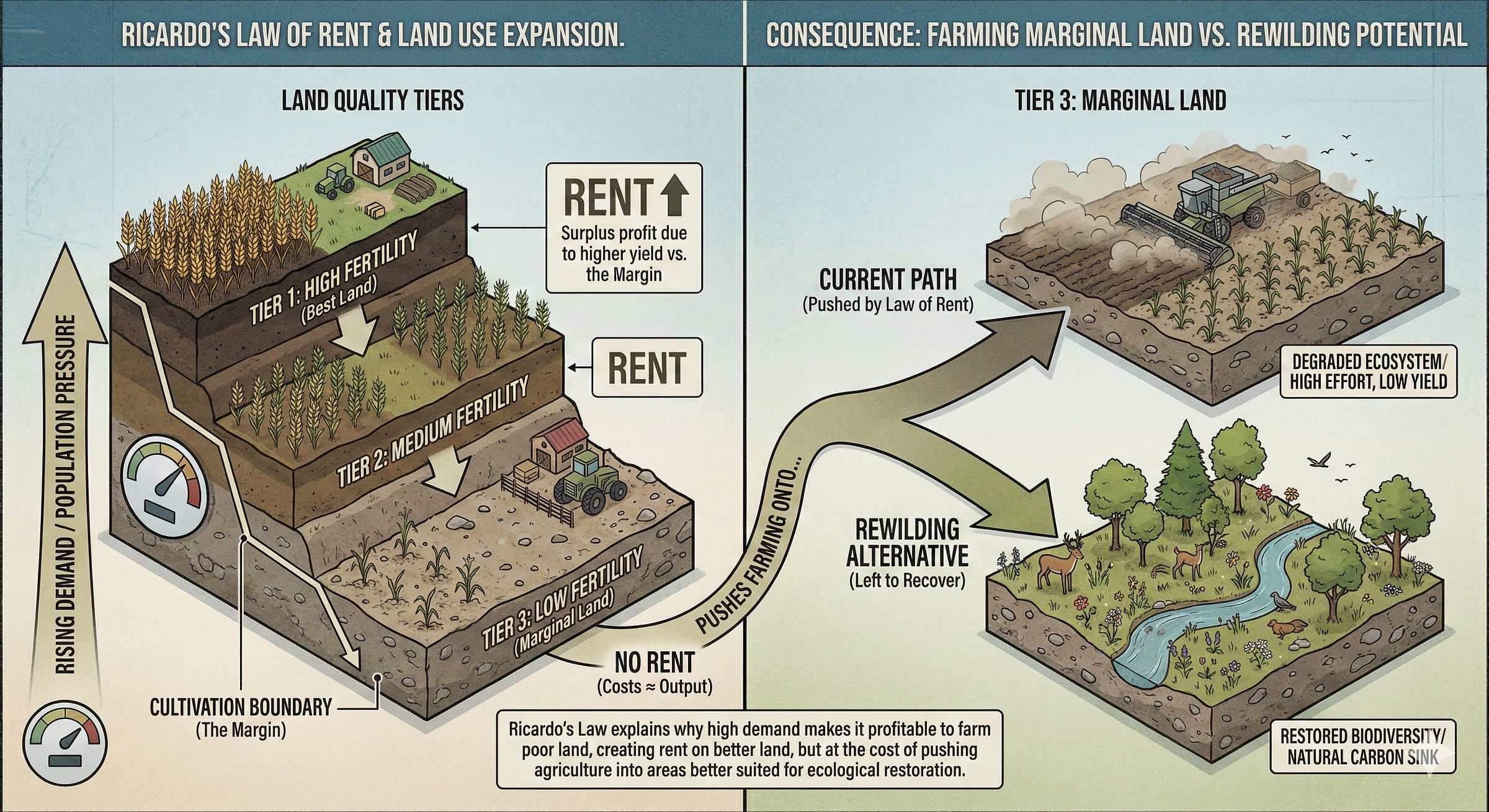

The interplay between economic theory and environmental practice is critical in understanding contemporary agricultural challenges. One key concept in this discourse is David Ricardo’s Law of Rent, a classical economic principle which posits that the economic return of land is determined by its fertility and location relative to the “margin of cultivation.” This principle not only dictates the expansion of farming onto increasingly poor-quality soils but also highlights a fundamental flaw in how modern economies generate public revenue.

In the United Kingdom, the natural economic progression is distorted by a complex framework of fiscal incentives that privatise economic rent while socialising environmental costs. Coupled with specific tax reliefs—particularly Inheritance Tax—and historical subsidy policies, the UK market incentivises the exploitation of land that is fundamentally uneconomic to farm. This essay explores how Ricardo’s Law of Rent drives farming practices toward poorer quality land and argues that the solution lies in a radical shift: treating Economic Rent not as private income, but as the rightful source of public revenue. By capturing rent and taxing externalities, we can reward genuine farmer ingenuity, retreat from marginal lands, and foster a massive resurgence in biodiversity.

Explainer: Ricardo’s Law of Rent

To understand the pressure on UK land, one must first grasp the mechanism of Ricardian Rent. David Ricardo, writing in the early 19th century, observed that rent is not an arbitrary price set by landlords, but a result of the differential productivity of land.

The Differential Nature of Rent

Ricardo defined rent as the portion of the produce of the earth paid to the landlord for the use of the “original and indestructible powers of the soil.” It arises because land is limited in quantity and variable in quality.

Imagine three grades of land:

Grade A (High Fertility): Can produce 10 tonnes of wheat with £1,000 of labour/capital.

Grade B (Medium Fertility): Can produce 8 tonnes of wheat with £1,000 of labour/capital.

Grade C (Marginal Land): Can produce 5 tonnes of wheat with £1,000 of labour/capital.

When the population is small, farmers only cultivate Grade A. Since there is abundant Grade A land, there is no competition, and essentially zero rent is paid. However, as the population expands, demand forces the price of wheat up, making it profitable to cultivate Grade B.

The moment Grade B is brought into cultivation, Grade A yields a surplus. Because the market price of wheat is now set by the production costs on Grade B (the new margin), Grade A farmers make a “super-profit” compared to Grade B farmers. This surplus becomes economic rent.

The Societal Nature of Rent

Crucially, this rent is not created by the landowner’s hard work or ingenuity. It is created by the community—by the demand for food from a growing population, and by the public infrastructure (roads, markets, security) that makes the land accessible. Therefore, Economic Rent is inherently a social surplus.

The Role of Economic Rent and Taxation

The central dysfunction in the UK economy is that we allow this socially created value (Rent) to be privatised by landowners, while the government funds public services by taxing the effort of workers and the risk of businesses (Income Tax, NI, Corporation Tax).

Rent as Public Revenue

A system based on capturing Economic Rent—often called a Land Value Tax (LVT)—is not technically “taxation” in the punitive sense. It is simply the community claiming the value it created.

Efficiency: Unlike taxes on income or capital, which discourage work and investment (creating “deadweight loss”), collecting rent does not distort economic activity. Land cannot be hidden, moved offshore, or stop working because it is taxed.

Justice: This system rewards active effort. The farmer who works long hours and innovates to increase yields keeps the fruits of their labour (their wages and profit on capital). They only pay the community for the exclusive right to hold the specific plot of land.

By failing to collect this rent, the UK encourages land speculation. Investors buy land not to farm it efficiently, but to capture the unearned increment of rising land values, often parking wealth in “tax-efficient” farmland that contributes little to the real economy.

How UK Tax and Subsidies Distort the Margin

Currently, rather than collecting rent, the UK tax system actively subsidises the holding of land, effectively “paying” landowners to occupy the margin.

1. The “Tax Shelter” Effect: Agricultural Property Relief (APR)

Under Agricultural Property Relief (APR), agricultural land can be passed down 100% tax-free (Inheritance Tax relief). This creates a massive incentive for High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) to purchase farmland as a tax shelter. This demand inflates land values far beyond what agricultural yields can justify, forcing owners to maintain token farming activity on marginal land just to satisfy HMRC rules.

2. Subsidising Failure (BPS Legacy)

For decades, subsidies were paid largely based on acreage. If a plot of marginal land costs £100 to farm but only yields £80 of produce, it is uneconomic. However, if the government provides a £50 subsidy, the farmer makes a profit. This artificial income stream pushes the Ricardian margin outwards, encouraging the destruction of nature on land that should naturally be wild.

The Destruction of Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity

This artificial extension of the agricultural margin forces nature into retreat, destroying the ecosystem services society relies upon.

1. Natural Flood Mitigation vs. The “Smooth Hill” Effect

Marginal lands, particularly uplands, are the country’s primary watersheds. Subsidised overgrazing compacts the soil and removes rough vegetation. The hills become “billiard tables” that shed water instantly, causing flash flooding in towns downstream.

2. Carbon Loss: Turning Sinks into Sources

Peatlands are drained and burned to make them suitable for grazing or shooting. Once drained, the peat oxidises, releasing millennia of stored carbon into the atmosphere. These lands become significant contributors to national greenhouse gas emissions rather than acting as carbon sinks.

3. Pollution and Biodiversity Loss

To force growth from poor soil, farmers apply nitrates and phosphates that wash off rapidly into rivers, causing eutrophication. Simultaneously, the removal of “unproductive” scrub to maximise eligible subsidy area has destroyed the habitat of pollinators and farmland birds, leading to a collapse in bio-abundance.

The Solution: A New Economic Settlement

To resolve these crises, we must realign the fiscal system with Ricardian principles and environmental reality. This involves a two-pronged approach: Collecting Rent and Taxing Externalities.

1. Shifting Taxes from Work to Rent

If the UK replaced taxes on labour and capital with a levy on Land Values (Rent), the economics of farming would be transformed.

The End of Speculation: Holding land as a tax shelter would become expensive. Landowners would be forced to use land productively or sell it to someone who can.

Efficient Allocation: Land would naturally fall into the hands of the most productive farmers—those with the ingenuity to produce high yields with minimal waste.

Rewilding the Margin: On marginal land (Grade 4 & 5), the potential agricultural rent is near zero. If the tax system recognises this, and subsidies for mere ownership are removed, it becomes economically irrational to force farming on these stony, wet, or steep terrains. This land would be released from agriculture, allowing it to rewild naturally at no cost to the taxpayer.

2. Externality Taxes: The “Polluter Pays”

Alongside collecting rent, the state must tax negative externalities—the harm done to the shared environment.

Nitrogen and Carbon Taxes: A tax on synthetic fertilisers and fossil-fuel inputs would reward farmers who farm with nature rather than against it. Farmers who use regenerative techniques to build soil fertility (reducing input costs) would gain a competitive advantage over those who rely on chemical inputs.

True Efficiency: This is not about punishing farmers; it is about accurate accounting. A farmer who produces cheap food by destroying the soil and polluting the river is not “efficient”—they are simply transferring their costs to the public.

3. Food Security and Prices

Critically, this shift would not threaten food security or raise prices. By concentrating farming on the most fertile (Grade 1 & 2) land—where inputs yield the highest returns—the UK can maintain high food output. Meanwhile, the cost of food remains stable because the “rent” component is recycled back to the public purse, reducing the tax burden on workers and businesses, leaving them with more disposable income.

Conclusion

Ricardo’s Law of Rent explains the pressure to expand agriculture, but it is our choice of tax base that turns this pressure into destruction. By taxing labour and capital while subsidising land ownership and pollution, the UK has created a system that rewards speculation and environmental degradation.

The remedy is to return to the root of economic efficiency: claim the Economic Rent for the public good. This would fund public services without penalising work, reward the ingenuity of genuine farmers, and allow the Ricardian margin to recede. The result would be a thriving, efficient agricultural sector on the best land, and a vast, natural restoration of the rest—a landscape where biodiversity recovers, carbon is stored, and floods are mitigated, all powered by the rational application of economic law.

Comments

Post a Comment