Thomas Cromwell, Georgism, Rewilding and the Lost English Utopia

Alternative History to Inspire Change?

Did Thomas Cromwell strive to revolutionise Britain to become an economic powerhouse, to abolish poverty and restore its declining wildlife? What could we learn from him today?

I have long harboured the idea that Thomas Cromwell was an early “Georgist” economist and proto rewilder, but this requires looking at the intersection of his real historical legislation and the modern interpretations popularised by historical fiction, most notably Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy and the scant evidence that exists that her did bring beavers back to the UK.

While the terms “Georgism” (coined in the 19th century) and “rewilding” (20th century) are anachronistic, Cromwell’s actions in the 1530s bear striking parallels to these modern concepts.

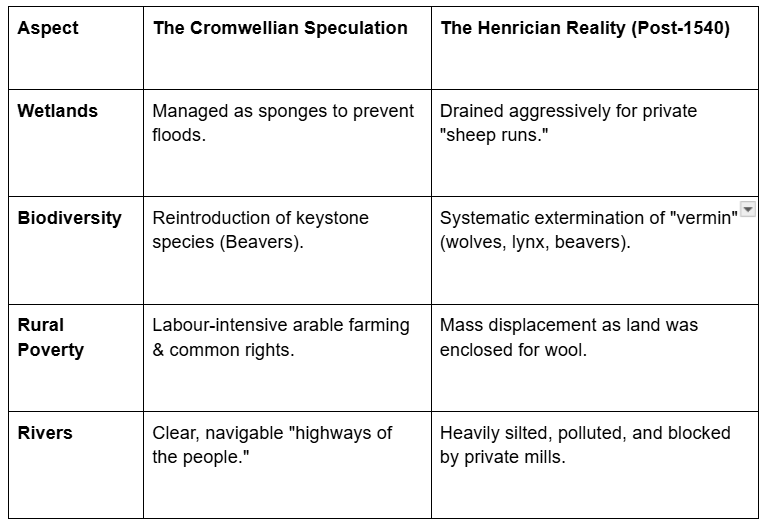

By viewing his actions through the lenses of Georgism and Rewilding, we can see a coherent (albeit lost) strategy for a modern England that might have avoided centuries of social and environmental strife. This speculative history posits a compelling counter-factual narrative for England, casting Thomas Cromwell’s ambitions in a radically new light. Far from being solely the cold-blooded, pragmatic bureaucrat often depicted, he emerges here as a frustrated visionary, a figure whose execution in 1540 represented not just a political downfall, but the tragic death of a comprehensive, state-managed strategy for a truly sustainable landscape and a more equitable society.

By deliberately reframing his actions, particularly the dissolution of the monasteries, through the analytical lenses of Georgism and Rewilding, a surprisingly coherent, albeit lost, strategy begins to take shape. This grand, unified plan, had it been allowed to mature, might have established a modern, resilient England, potentially circumventing centuries of subsequent social fragmentation, environmental degradation, and the deeply entrenched economic strife that followed.

The Georgist Dimension: Land as Public Wealth

The Georgist critique, centred on the idea that the economic rent derived from land’s inherent value should belong equally to all members of society, finds an echo in Cromwell’s land reforms. The dissolution was a radical redistribution, breaking the inert grip of the Church, which held an estimated one-fifth of the nation’s wealth. A true Cromwellian vision, informed by this Georgist spirit, might have seen this vast monastic estate nationalised in perpetuity, or leased out with the rent flowing directly to the Crown for public works and welfare, rather than being sold off wholesale to create a new, rapacious class of landed gentry. His early attempts to survey and value these lands suggest an unprecedented desire for granular, state-level knowledge, a prerequisite for any systematic, Georgist-style land-value-based taxation and public management.

The Rewilding Dimension: The Monastic Estate as a State-Managed Reserve

Furthermore, the scattered, often ecologically rich and lightly managed lands of the monastic orders, forests, wetlands, and upland pastures could have been preserved and managed not as intensive agriculture, but as vast ecological and hydrological reserves. Seen through a modern ‘Rewilding’ lens, Cromwell’s seizure of these lands offered a unique, historical opportunity to establish a state-managed ‘national nature reserve network’ centuries ahead of its time. The monasteries, despite their flaws, often protected ancient woods and traditional, low-intensity farming methods. Their dissolution and subsequent enclosure accelerated the clear-felling and intensive exploitation of the landscape. A visionary Cromwell, grasping the long-term strategic value of ecosystem services, could have mandated the retention of these estates for timber, water management, and the preservation of biodiversity, ensuring the long-term ecological health of the realm.

In this counter-factual timeline, Cromwell’s vision marries economic equity with ecological foresight. His execution in 1540 thus became the pivotal moment when England chose the short-term profits of aristocratic enclosure and laissez-faire land ownership over a sustainable, truly efficient future, a choice whose consequences continue to define the nation’s landscape and socio-economic divides to this day.

1. The Cromwellian “Common Weal” as Proto-Georgism

In UK economic history, the “Common Weal” was the idea that the state exists to ensure the prosperity of all. Cromwell’s attempt to nationalise monastic land was the closest England ever came to a Georgist “Single Tax” model.

The Land as a Perpetual Endowment: Cromwell’s original plan for the Court of Augmentations was to keep monastic lands in the hands of the Crown. If the state had remained the primary “landlord,” the rent and production value would have funded the government indefinitely. This would have potentially replaced the need for the “Poll Taxes” and “Hearth Taxes” that burdened the poor for centuries.

Taxing Unearned Increment: Through the Statute of Sewers, Cromwell established that if the state improved your land (via drainage or flood defence), you owed the state a “scot” or tax. This is purely Georgist: the community-created value of the land should be returned to the community.

The “Great Privatisation”: When Henry VIII executed Cromwell and sold the land to the Gentry to fund his wars in France and palatial homes, he effectively “locked in” the class system. The value of England’s soil shifted from a public benefit to a private asset, leading directly to the Highland Clearances and the Enclosure Acts of later centuries.

2. Beavers and the “Natural Infrastructure” Dream

If we elaborate on the “Rewilding” speculation, Cromwell’s import of beavers from the Baltic (Danzig) suggests he was looking for a solution to a specific Tudor crisis: The collapse of the river systems.

The Beaver as a “Civil Servant”: In this speculative view, Cromwell, who was obsessed with efficiency, saw beavers as a self-maintaining labour force. Unlike human-built dams, beaver dams are “leaky”; they slow down water to prevent downstream flooding while maintaining a constant water table that keeps the surrounding land fertile during droughts.

The “Natural Infrastructure” Argument: Historians speculate that Cromwell’s hatred of water mills and fish weirs (which he ordered demolished across the UK to improve navigation and fish stocks) shows he favoured “living” water systems. If one speculates through a rewilding lens, beavers would have been the perfect tool for his goals: they create wetlands that mitigate flooding and restore salmon runs, exactly what Cromwell’s commissions were trying to achieve through legislation.

The Menagerie as a Pilot Project: While most nobles kept exotic animals for prestige, speculation suggests Cromwell, a man of obsessive practicality, may have viewed his private collection as a laboratory. Importing a species that had been extinct in England for centuries (the Eurasian beaver) suggests an interest in the “functional” restoration of the landscape.

3. The Consequences of the “Henry VIII Turn”

The shift from Cromwell’s “Managed Common Weal” to Henry’s “Privatised Enclosure” created a domino effect of ecological and social decay that defined the UK for 400 years:

The Ecological “Great Stink”

By choosing the path of privatisation, the English landscape was stripped of its natural resilience. The removal of wetlands (the “kidneys” of the landscape) meant that when the Little Ice Age hit in the 17th century, the UK suffered from unprecedented flooding and crop failures. Cromwell’s beavers, had they been released and protected, might have mitigated the worst of this by regulating the flow of the major river catchments like the Thames, the Severn, and the Trent. The Ecological “Great Stink” This speculation directly relates to the challenges we face today.

The trajectory towards the privatisation of land in England irrevocably stripped the national landscape of its inherent, natural resilience. This shift in land management priorities often favoured intensive agriculture and development over ecological function, leading to catastrophic consequences. Often we use the term intensive agriculture but this is a misnomer, common land was often far more productive in terms of food yet protected nature far better, The new intensive systems drove labour from the land and promoted low labour systems such as cash crops or sheep that destroyed the ecological character of land but actually provided less food, instead just providing cash crops for the rich land monopolists. In a broader view, this era saw the widespread drainage and removal of crucial wetlands, often referred to as the “kidneys” of the landscape. These ecosystem services, vital for water purification, carbon sequestration, and, most importantly, natural flood control, were systematically eliminated.

A poignant historical counterfactual highlights the short-sightedness of the prevailing land-use policy: the potential role of beavers. Had Thomas Cromwell’s earlier, tentative efforts to reintroduce beavers been sustained, protected, and allowed to proliferate, the situation might have been drastically mitigated. These ecosystem engineers, through their dam-building activities, create complex, multi-layered wetland systems. They slow the flow of water, spread flood pulses across wider areas, and create deep pools that sustain river life during drought. Had they been actively managing the flow dynamics of major river catchments, such as the mighty Thames, the powerful Severn, and the crucial Trent, the intensity and duration of the subsequent environmental crises could have been significantly lessened, offering a critical natural defence against the meteorological extremes.

The Social “Great Dispossession”

The enclosure of the land didn’t just hurt the environment; it broke the British spirit of the “Common.” Without the ability to graze a cow or forage in a wetland, the peasantry was forced into the cities, providing the “surplus labour” that fueled the often-brutal early Industrial Revolution. The Social “Great Dispossession” and the Birth of the Industrial Proletariat

The enclosure movement, an economic and legal transformation focused on privatising formerly common lands, enacted a profound social and spiritual rupture that extended far beyond mere ecological damage. This systematic dismantling of the ancient manorial system constituted a “Great Dispossession,” fundamentally altering the relationship between the British populace and the soil.

The traditional rural economy was underpinned by the concept of the “Common,” which, while often romanticised, was a vital safety net and resource base for the peasantry. It granted them crucial, if limited, rights: the estovers (the right to cut wood), the turbary (the right to cut peat for fuel), and, most critically, the right of common of pasture (the ability to graze a cow, a few geese, or a pig). With the advent of parliamentary enclosures, these ancestral and customary rights were extinguished. The smallholder and the landless labourer were stripped of the ability to sustain themselves independently. The loss of a patch of common ground meant the effective loss of their subsistence, the ability to graze a cow for milk, forage in a wetland for supplementary food, or gather firewood.

This economic devastation left the rural working class with a stark and brutal choice: starve or migrate. Consequently, masses of dispossessed, newly landless individuals were forced to abandon their ancestral villages and flood into burgeoning urban centres. This demographic shift provided the essential component for the nascent factory system: a large, available pool of easily exploitable labour. This influx generated the very “surplus labour”, a term of political economy for a workforce exceeding immediate demand, that became the indispensable human fuel for the often-brutal and transformative early stages of the Industrial Revolution. This newly formed, propertyless urban class, the proletariat, had nothing to sell but its own labour, thereby establishing the fundamental social conflict and economic structure that would define the modern age.

The Road Not Taken: Cromwell, Economic Rent, and the High-Technology Utopia

In the 16th Century Thomas Cromwell and perhaps even his distant descendant in the mid-17th century, Oliver Cromwell, represented a profound and ultimately frustrating turning point in Britain’s economic and social destiny. Economists and historians have long speculated on a radical, alternative future, a trajectory predicated on a fundamental restructuring of the nation’s revenue system. This speculative history suggests that if both Cromwells had successfully established a commonwealth where the economic rents, the unearned income derived from the monopoly ownership of land and natural resources, were retained as public revenue, Britain might have transformed into a high-technology, socially progressive utopia.

Both Cromwells, it is posited, were acutely aware of historical precedent. They understood that previous successful taxation systems, which claimed the nation’s rents for the public purse, had functioned effectively to fund the state and public services without burdening productive labour. Conversely, he would have recognised that the privatisation of economic rent, the system that allowed a landed aristocracy to appropriate this value, was historically a recipe for national disaster, leading to increased inequality, speculative booms and busts, and the stifling of innovation due to high taxation on industry and trade. By capturing this unearned increment, a Cromwellian state could have eliminated taxes on labour, capital, and industry, freeing up immense productive capacity and providing the necessary capital for monumental public investment in science, infrastructure, and education, the very foundations of a high-technology future.

The Decisive Shift: Privatisation and Empire

However, the historical path ultimately chosen by Britain, both immediately following Thomas Cromwell’s execution and the Restoration after Oliver Cromwell, saw the solidifying over the subsequent centuries, was precisely the opposite. The nation decisively moved to privatise economic rents, cementing the financial power of the landowning elite and laying the foundation for a system of deep, structural inequality. This model, where the wealth generated by the community’s growth flowed into private, unearned fortunes, demanded an alternative means of state finance, necessitating the imposition of burdensome taxes on productive economic activities.

This internal economic decision had vast and devastating external consequences. Having established a domestic model that systematically siphoned wealth from production into private land monopolies, Britain then had an urgent, structural requirement to seek external wealth and resources to fuel its growth and maintain its geopolitical dominance. The decision to privatise economic rents and consequently burden the working population was intrinsically linked to the national imperative to expand. This flawed domestic economic structure then served as the primary engine driving the expansion of the British Empire.

Britain subsequently expected this rent-privatising model to serve as the dominant global paradigm. The empire was not merely a military and political project but an economic one, designed to either physically enslave large swathes of the world’s population into serving the metropolitan economy or, through political and economic pressure, set an irresistible example to other emerging countries. The aim was to ensure that the global economic structure mirrored the domestic one: a system where resources and land were monopolised, and the wealth generated by human ingenuity and labour was controlled by a privileged few, first in England, and then in the satellite ruling classes of its dependencies. This legacy, the failure to capture the nation’s rents for public good, is arguably the defining economic characteristic that shaped Britain’s social stratification, its political history, and its global impact.

Peter Smith

2026

Comments

Post a Comment