Green Deserts & Paper Profits: The True Cost of UK Land Wealth - and how to fix it...

A Fifty-Year History of UK Land Values: From Productive Asset to Financial Monopoly

Introduction: The Great Decoupling

Over the past fifty years, land in the United Kingdom has undergone a fundamental transformation. What was once primarily a factor of production—an asset valued for its ability to grow food, provide timber, or support a home—has evolved into a financial asset class in its own right. The value of UK land has dramatically decoupled from the productive economy, with prices now driven less by agricultural yield or construction costs and more by fiscal policy, credit supply, and, most recently, the nascent markets for “Natural Capital.” This report traces this fifty-year journey, revealing how a powerful, often invisible, architecture of tax incentives, subsidies, and planning laws has inflated land values, with profound consequences for wealth inequality, homeownership, and nature conservation. We will explore the macro-trends that have seen marginal land outperform prime real estate, dissect the specific policy drivers behind this inflation, and analyse the impact across agricultural, residential, and conservation sectors. Finally, the report will examine the socio-economic consequences of this shift, culminating in an analysis of the current market at a critical crossroads.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. The Macro Trend: Visualising a Half-Century of Divergence

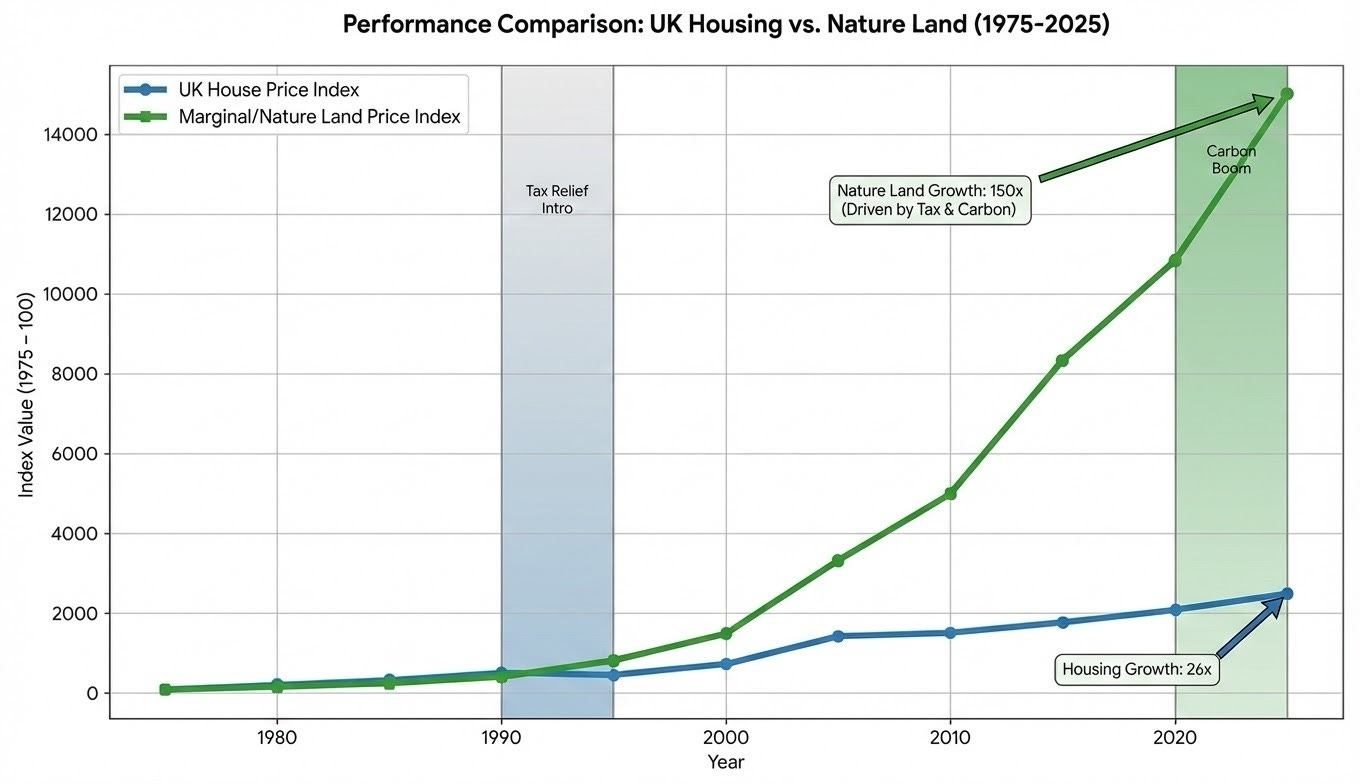

To comprehend the scale of the transformation in the UK land market, it is essential to visualise the long-term trends. Comparing asset performance over decades reveals deep structural shifts that short-term analysis can miss. This section compares the price growth of what we term “Nature Land”—marginal, upland, and scrubland suitable for conservation—against the more familiar UK housing market. The results illustrate a dramatic and often overlooked divergence, where the country’s least productive land has become one of its most lucrative financial assets.

Performance Comparison: UK Housing vs. Nature Land (1975–2025)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Key Takeaways from the Data

● The “Golden Era” (1975–1990): The analysis begins with a period of relative stagnation for Nature Land Values. As the green line on the chart shows, its value remained almost flat. During this era, land’s worth was inextricably tied to its agricultural productivity; if it could not grow food or support livestock, it was considered effectively worthless. This stands in stark contrast to the UK housing index (blue line), which rose steadily with inflation, reflecting the consistent demand for shelter. This period represented a “Golden Era” for conservation buying, when land for nature was abundant and cheap.

● The “Tax Shelter” Take-off (1992–2008): A sharp inflection point occurs in the green line around 1995. This dramatic shift is directly correlated with the introduction of 100% Agricultural Property Relief (APR) in 1992. This tax policy transformed marginal land from a simple physical asset into a highly effective tax shield for passing on wealth free of Inheritance Tax. Suddenly, the financial yield of the tax break far outstripped any potential agricultural yield. This attracted a new class of wealthy buyers, causing Nature Land values to not only rise but begin to significantly outperform the housing market.

● The “Carbon Rocket” (2020–2025): The most recent period is defined by a near-vertical spike in the value of Nature Land. While housing price growth slowed in response to rising interest rates, the green line accelerated exponentially. This “Carbon Rocket” phase was ignited by the financialization of the biosphere. A parcel of land no longer had just one utility (e.g., grazing); it could now provide a “stack” of monetizable services, including Carbon Credits, Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) units, and tax relief. This stacking of new financial utilities on top of existing benefits caused prices to detach from all previous fundamentals, effectively pricing traditional buyers and conservation charities out of the market.

This extraordinary divergence is best illustrated with a simple investment comparison. An investment of £10,000 in a UK house in 1975 would be worth approximately £270,000 today. The same £10,000 invested in Scottish hill land would be worth an astonishing £1.5 million. The following sections will delve into the specific economic and policy mechanisms that drove this outcome.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2. The Invisible Architecture: Causal Drivers of Land Value Inflation

Land values do not rise in a vacuum. Their trajectory is shaped by a powerful, often invisible, architecture of financial and policy decisions. While market forces play a role, the fifty-year inflation of UK land prices has been predominantly driven by structural factors related to money supply, tax policy, agricultural subsidies, and the planning system. This section dissects these four primary drivers to explain how they have collectively turned UK land into one of the world’s most secure and fastest-growing asset classes.

2.1 The Primacy of the Land Monopoly in Monetary Expansion

There is a near-perfect correlation between the UK’s broad money supply (M4) and land values, a relationship governed by the monopolistic nature of land itself. As commercial banks create new money through the issuance of mortgage debt, this flood of fresh credit enters the economy to chase a strictly finite asset. However, the creation of this liquidity is no longer the sole preserve of commercial banks issuing traditional mortgage debt. Today, the flood of credit is intensified by exotic offshore financial systems, shadow banking, and increasingly, the volatile wealth generated by cryptocurrencies. This vast, globalised capital enters the local economy to chase a strictly finite asset. Because the supply of land is fixed and cannot expand to meet this demand, it functions as a natural monopoly, absorbing this excess liquidity entirely through price inflation.

Because the supply of land is fixed and cannot expand to meet this demand, land functions as a monopoly, absorbing the excess liquidity entirely through price inflation. Consequently, the “cost” of a home, farm or nature reserve is divorced from the physical price of bricks and mortar or productivity; instead, it becomes a measure of the maximum debt the ‘banking’ and now ‘shadow banking’ sector is willing to leverage against the scarce earth beneath it in the light of the tax breaks, subsidies.

As Peter Smith summarises:

“We have reached a point where the market value of land has nothing to do with its utility. Ultimately, the question ‘how much is land worth?’ has a simple, brutal answer: it is worth every penny of credit or capital you can access—from any source, anywhere in the world—pitted against every penny available to your competitor. We are no longer paying for the soil; we are paying for the monopoly.”

2.2 Taxation as a Price Support

Decades of fiscal policy have systematically transformed UK land, particularly agricultural and residential land, into a highly effective tax haven. This has artificially inflated prices by creating demand from individuals seeking to shelter wealth from the tax man.

● Agricultural Property Relief (APR): Introduced in its current 100% relief form in 1992, APR allows qualifying agricultural land and property to be passed on completely free of Inheritance Tax. This has created a powerful incentive for wealthy individuals to purchase farmland not primarily for farming, but as a vehicle for tax-free intergenerational wealth transfer. This effect creates a significant 20-30% “tax premium” on land prices, forcing all buyers to pay a price well above the land’s productive value.

● Capital Gains Tax (CGT): The exemption of a primary residence from CGT encourages over-investment in housing. It makes the family home the most tax-efficient vehicle for wealth accumulation for most of the population, channelling savings into housing land and further inflating its value.

● Income Tax on Timber: In a unique anomaly within the UK tax system, profits generated from the sale of timber from commercial woodlands are 100% exempt from Income Tax. This makes forestry a uniquely attractive shelter for high earners, adding yet another layer of financial demand to a specific land class.

2.3 The Capitalisation of Subsidies

The economic mechanism of capitalisation ensures that any consistent, long-term revenue stream linked to a fixed asset is ultimately absorbed into that asset’s market price. For instance, the area-based subsidies of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) provided a guaranteed income for land ownership that failed to benefit working tenant farmers; instead, these payments were capitalised directly into the land’s value. This transformed land into a “risk-free bond,” establishing an artificial price floor that serves the landowner exclusively at the point of disposal. This systemic process is identical for all forms of state intervention, including tax breaks and public infrastructure investments, which are invariably “mopped up” by the land market. Consequently, resources intended for environmental conservation, wildlife charities, or social welfare are effectively captured by land monopolists and the financial institutions that advance credit for land purchases. Such institutionalised cheating allows the asset-rich to act as free riders, siphoning off publicly created value while the working population is forced to subsidise these windfalls through “mortal taxes” on their own labour.

2.4 The Planning System as Scarcity Engine

The UK’s restrictive planning system is the single most powerful driver of residential land values. By severely limiting the supply of land with permission to build, it creates a condition of extreme artificial scarcity. This generates an extraordinary multiplier effect on value. Agricultural land with a typical market value of £10,000 per acre can see its price jump to between £1 million and £4 million per acre the moment it receives planning permission. The value is not in the physical land itself, but in the state-granted monopoly right to build upon it.

These four drivers—credit, tax, subsidies, and planning—have worked in concert to create the market conditions we see today. The next section will explore how their effects have manifested across different sectors of the UK land market.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3. A Sector-by-Sector Analysis: Four Markets, One Trend

While the overarching drivers of land value inflation are consistent, their effects manifest differently across the UK’s various land types. The interplay of tax incentives, planning rules, and new environmental markets has created distinct trajectories for agricultural, residential, conservation, and woodland assets. This section provides a detailed historical analysis of these four primary land market sectors, revealing how a single trend—the financialization of land—has reshaped each in unique ways.

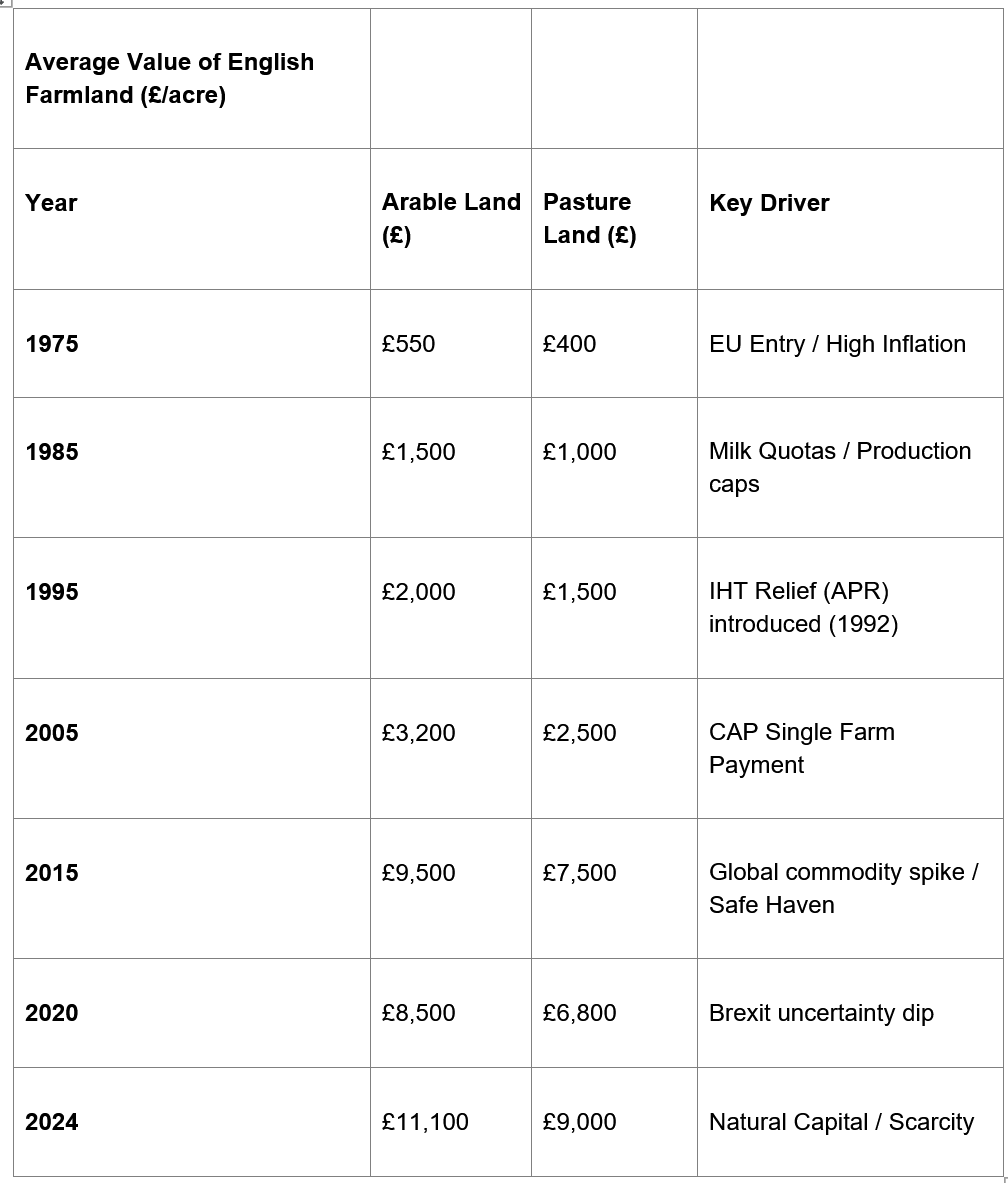

3.1 Agricultural Land: From Food Production to Financial Shelter

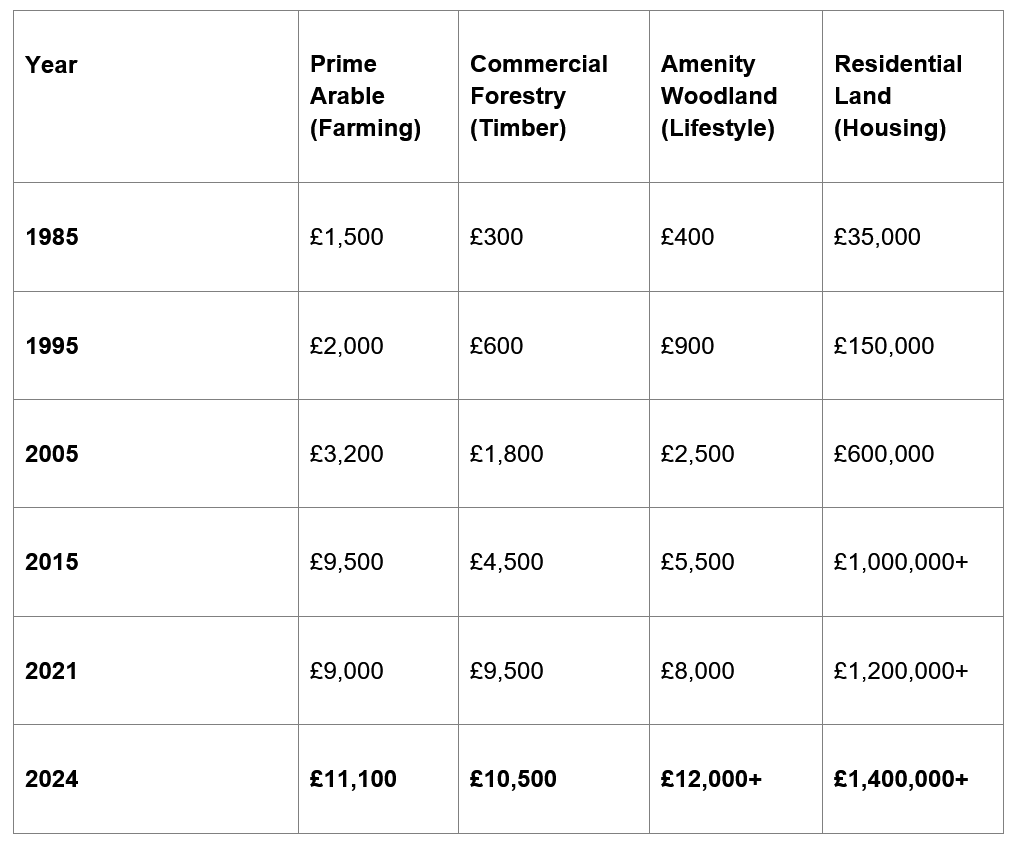

The value of UK farmland has completely decoupled from the income that can be generated by farming it. Once priced according to commodity yields and soil quality, its value is now predominantly determined by its effectiveness as an Inheritance Tax shelter, its “safe haven” status for investors, and its potential to generate income from “green finance.” The table below illustrates a shallow price incline until the late 1990s, followed by a steep climb as tax reliefs and subsidies took hold.

Average Value of English Farmland (£/acre)

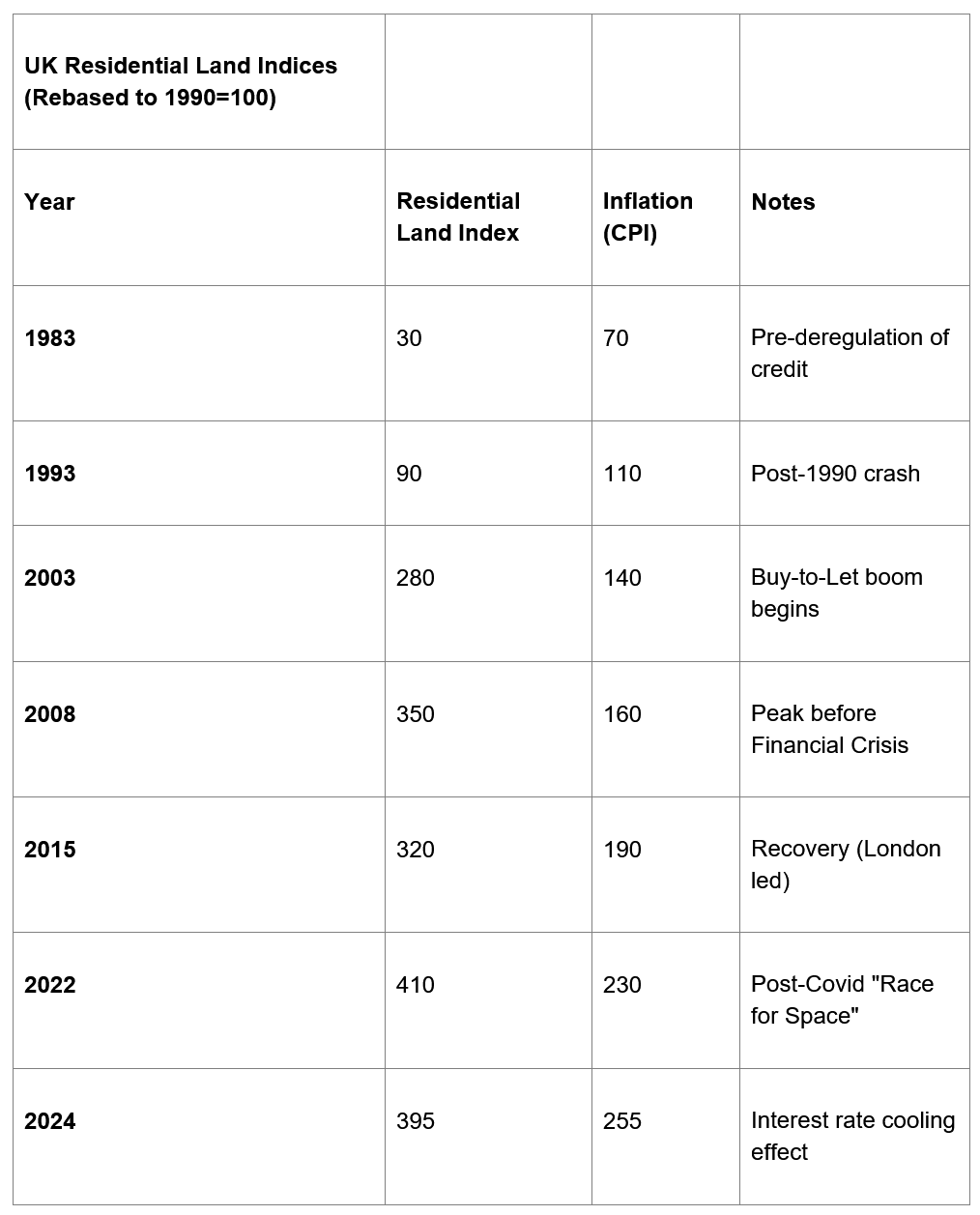

3.2 Residential Land: The Monopoly of Permission

The residential land sector is the most extreme example of a land monopoly in action. The value of a plot lies almost entirely in the state-granted planning permission attached to it. As the data shows, the growth in residential land values has vastly outstripped general inflation, driven by the combination of an expanding credit supply and a tightly restricted planning system. This exponential curve demonstrates that high house prices are, in essence, a reflection of high land prices.

UK Residential Land Indices (Rebased to 1990=100)

The data reveals that since 1990, residential land values have risen roughly 4x faster than general inflation (CPI), absorbing a vast share of the nation’s economic growth.

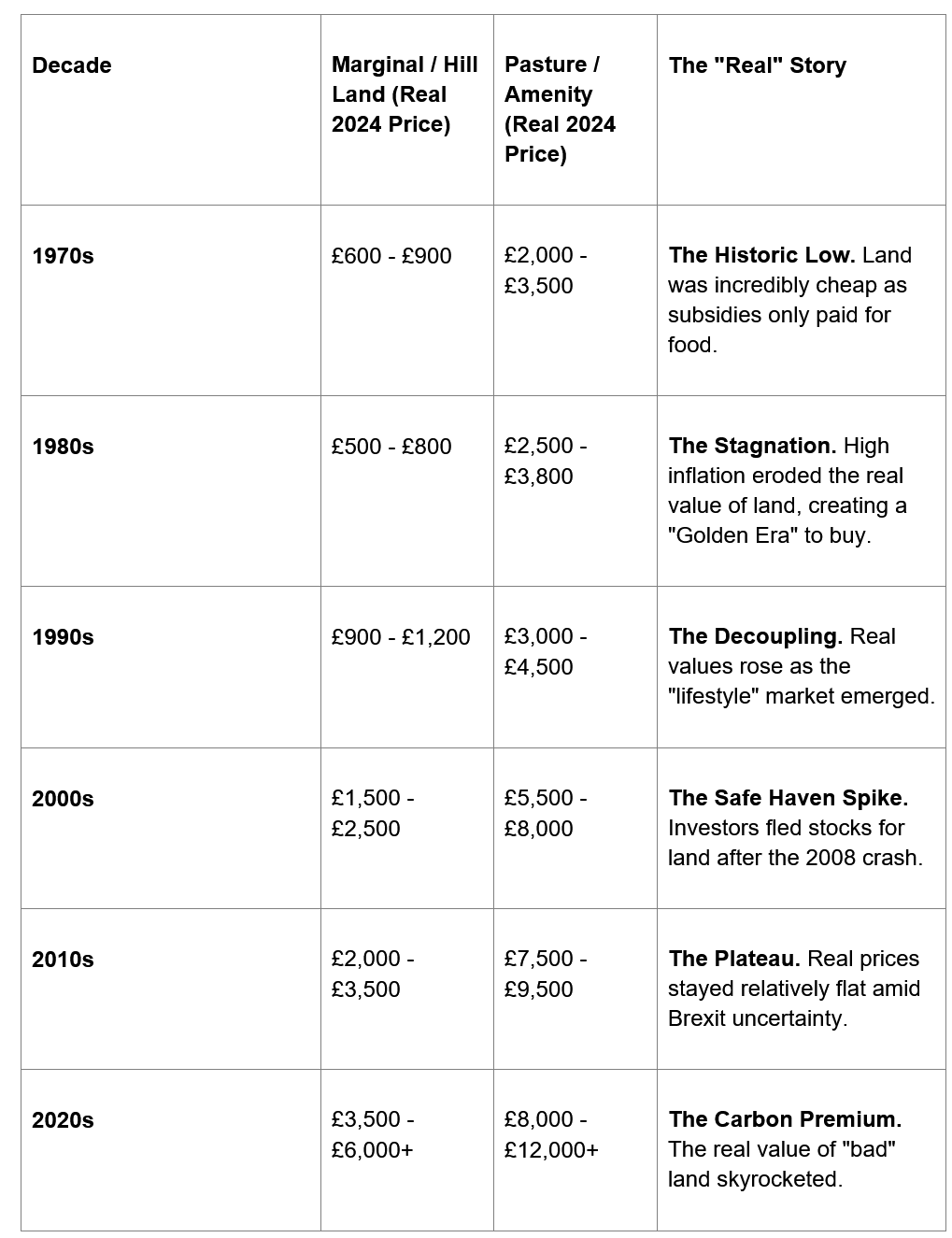

3.3 Conservation & Amenity Land: The Real-Term Price Explosion

Historically, the cheapest category of land—comprising uplands, marshes, and scrub—conservation land has seen the most dramatic price explosion in real terms. Adjusting for inflation reveals that its value was not just nominally low in the past; it was significantly cheaper in terms of real purchasing power. The 1980s, when high inflation eroded the real value of a stagnant land market, represented a “Golden Window” for conservation acquisitions. Today, the real cost of securing land for nature has risen by over 600% since 1975, driven first by “lifestyle” buyers and now by “Natural Capital” investors.

The Inflation-Adjusted Table (Per Acre) Prices adjusted to 2024 Equivalent Purchasing Power

3.4 Woodland: The Tax and Carbon Haven

Woodland has transformed from one of the cheapest land types into a premier asset class. This surge has been powered by a unique combination of generous tax reliefs and the new demand for carbon offsetting. In a major market shift, the value of commercial forestry land overtook prime arable land for the first time in 2021, signalling that the financial yield from trees and tax benefits now exceeds that from food and farming subsidies. While Commercial Forestry values first surpassed Prime Arable in 2021, a subsequent cooling in the forestry market and continued strength in arable land have seen the latter regain a narrow lead by 2024, highlighting the volatility of the new ‘green asset’ class. This trend is split regionally: Scotland has become an industrial-scale “Carbon Factory” for institutional investors, while the South East sees extreme prices driven by “Hope Value”—speculation on future development potential.

Comparative Land Values (1985–2024). Values are average per acre.

The sector-specific analyses demonstrate how different policy levers have produced similar outcomes across the board: higher prices, decoupling from productive use, and a shift toward land as a financial instrument. This trend has been supercharged by the most recent and powerful driver: the “Green Rush.”

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4. The “Green Rush”: Financialising the Biosphere (2020–Present)

The period from 2020 onwards marks a revolutionary shift in UK land valuation. The traditional logic, where value was derived from what the land could produce, was inverted. What was once considered an agricultural liability—unproductive scrub, boggy marsh, or steep hillsides—has been redefined as a high-yield financial asset. This rapid transformation has been driven by the monetisation of ecosystem services, creating a speculative “Green Rush” as investors seek to capitalise on the new markets for environmental credits.

4.1 The New Valuation Model: Stacking Carbon, Biodiversity, and Nutrients

The new valuation model is based on the concept of “stacking”—generating multiple, distinct revenue streams from different environmental credits on a single parcel of land. The three main credit types are:

● Carbon Credits: Issued under official schemes like the Woodland Carbon Code and Peatland Code, these credits represent a verified tonne of sequestered CO₂. They are purchased by corporations to offset their emissions as part of “Net Zero” strategies.

● Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG): As of 2024, property developers in England are legally required to deliver a 10% net gain in biodiversity. If they cannot achieve this on-site, they must buy “BNG Units” from landowners who are creating or enhancing habitats elsewhere.

● Nutrient Neutrality: In specific protected water catchments, developers must offset the pollution (nitrates and phosphates) from new housing. They do this by purchasing credits from landowners who take land out of production to reduce agricultural run-off.

4.2 Market Impact and Price Distortion

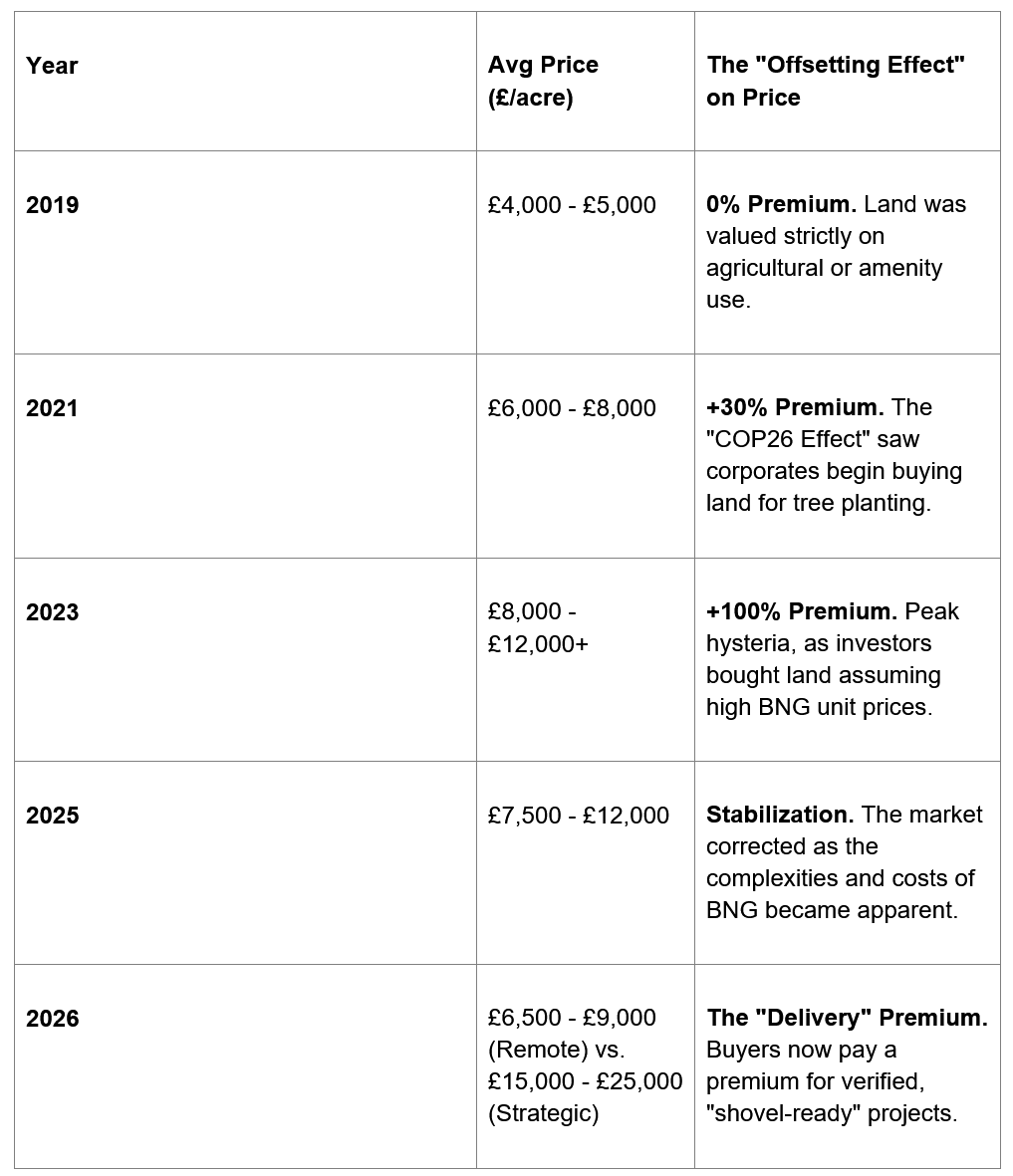

This new model rapidly distorted the market for marginal land. Prices surged based on the “hope value” of future credit sales, creating a speculative bubble. The table below charts the impact of this offsetting effect on land prices, showing a period of “peak hysteria” in 2023 when the premium for land with offsetting potential reached over 100%, followed by a market correction as the practical realities of delivering these credits became clear.

The “Green Premium” Table: Land Prices & Offsetting Impact (2019–2026) Prices refer to “Planting/Natural Capital” land (marginal pasture/uplands).

The “Delivery” Premium. Buyers now pay a premium for verified, “shovel-ready” projects.

A key distortion has been the BNG “Location Lottery.” Unlike carbon, biodiversity units are not fungible. Developers are penalised for buying offsets far from their construction sites, creating micro-markets where land near development hubs can trade at prices akin to development land itself, while demand in remote areas is near zero.

4.3 A Worked Example: Valuing “Worthless” Land

The profound shift in valuation is best illustrated with a hypothetical 50-acre plot of poor-quality marginal land.

The result is that this “worthless” scrubland, based on the capitalised value of its potential environmental credits, is now worth 3x to 4x more than prime, food-producing arable land. This inversion has profound consequences for our economy and society.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5. The Consequences: A Nation of Rentiers

The profound financial and policy shifts detailed in this report have had significant real-world socio-economic consequences. The relentless inflation of land values has created a purchasing power crisis for those seeking to conserve nature, while simultaneously cementing a deeply unequal pattern of ownership. Land’s evolution into a financial monopoly has widened the gap between asset owners and the landless, creating what is increasingly a nation of rentiers.

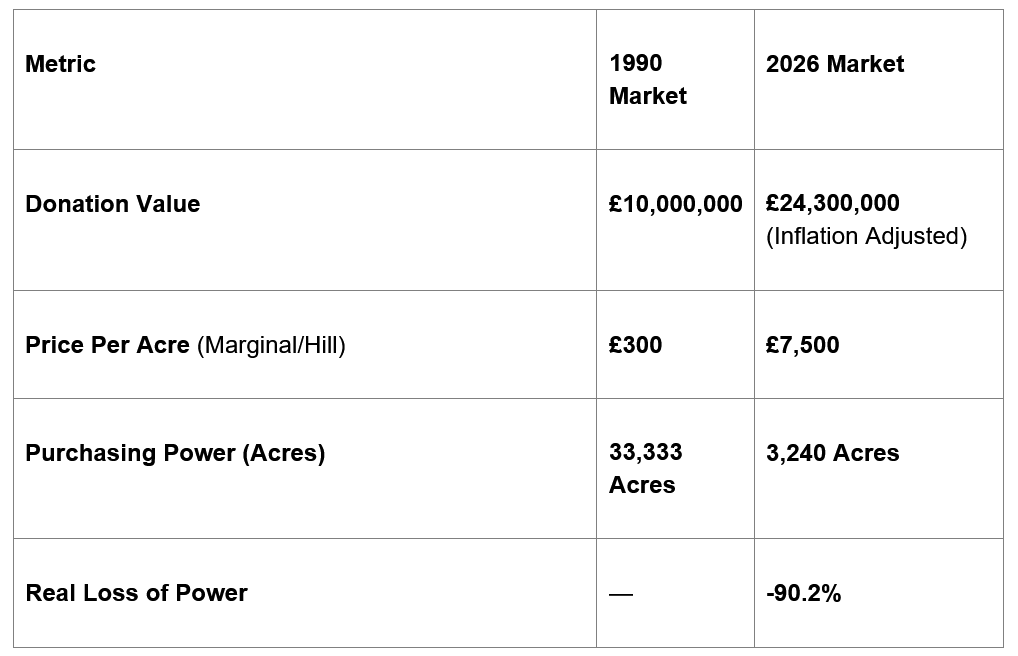

5.1 The Conservation Purchasing Power Crisis

While land has become a lucrative asset for investors, its price inflation has crippled the ability of environmental charities to acquire and protect it. The cost of “nature-suitable” land has risen far faster than general inflation, meaning that charitable donations have suffered a catastrophic loss of real purchasing power.

The “Nature Acre” Collapse Modelling a £10 million donation from 1990 to 2026.

This represents a staggering -90.2% real loss of purchasing power. To visualise this collapse: in 1990, a £10 million donation could have purchased an area the size of Bristol. In 2026, its inflation-adjusted equivalent can barely acquire an area the size of Heathrow Airport.

This stark economic reality has necessitated a fundamental strategic shift across the UK conservation sector. The traditional “Acquisition” model, focused on the outright purchase of land, has become mathematically unviable for all but the most critical sites, as the real purchasing power of charitable endowments has collapsed by an estimated 90.2% since 1990.

In its place, a “Covenanting” model has emerged; in high-cost economies like the UK, it is often considered economically inefficient for charities to own the soil when they can achieve more biodiversity per pound through management agreements and “Landscape Recovery” partnerships. For example, the £7.5 million required to purchase 1,000 acres of land today would generate enough interest to pay a farmer a generous salary to manage that land for nature without the charity ever needing to acquire the freehold.

However, this forced pivot has arguably hampered the ability to protect wildlife, as conservation bodies are now structurally disadvantaged. Charities, which are tax-exempt, must compete against wealthy individuals who treat land as a tax shelter, paying a “tax premium” of 25–30% for Agricultural Property Relief, and corporate investors who can pay vastly higher prices based on 50-year speculative carbon returns. This financialisation of the countryside, or the “Green Rush,” has turned “useless” marginal land into a high-priced asset class, further pricing out conservationists and contributing to the continuing loss of UK biodiversity.

5.1 The Efficacy Gap in Environmental Markets

Compounding the purchasing power crisis is the growing concern that the financialisation of nature is delivering poor ecological outcomes. While “Natural Capital” markets promise to fund restoration, the reality is often a triumph of marketing over biology.

● The Carbon/Soil Paradox: The current carbon market often relies on flawed baselines. Evidence suggests that planting trees on carbon-rich pasture or peatlands disrupts the soil structure, releasing significant amounts of stored carbon into the atmosphere. It can take a new plantation twenty to thirty years just to re-absorb the carbon released during its own creation, resulting in a net-negative impact on the climate in the short term.

● The Creation of “Green Deserts”: The regulations driving these markets frequently fail to distinguish between a functioning ecosystem and a mere plantation. To maximise financial returns, landowners often plant fast-growing or single-species crops. These habitats are ecologically brittle, lacking the complexity to support a food web, effectively creating “green deserts” where wildlife cannot survive.

● The Management Deficit: There is a distinct lack of long-term stewardship. Because the financial reward is often triggered by the act of planting rather than the long-term success of the habitat, management is frequently outsourced to the lowest bidder. This results in high sapling mortality rates and habitats that are managed to a minimum contractual standard rather than for maximum ecological health.

● The Middleman Economy: Perhaps most damaging is the leakage of capital. A significant percentage of the money destined for nature recovery is absorbed by a burgeoning industry of brokers, verifiers, and consultants. These middlemen enrich themselves on the complexity of the market, diverting funds that should be spent on practical conservation on the ground.

5.2 The Monopoly Effect: Ownership, Inequality, and the Broken Ladder

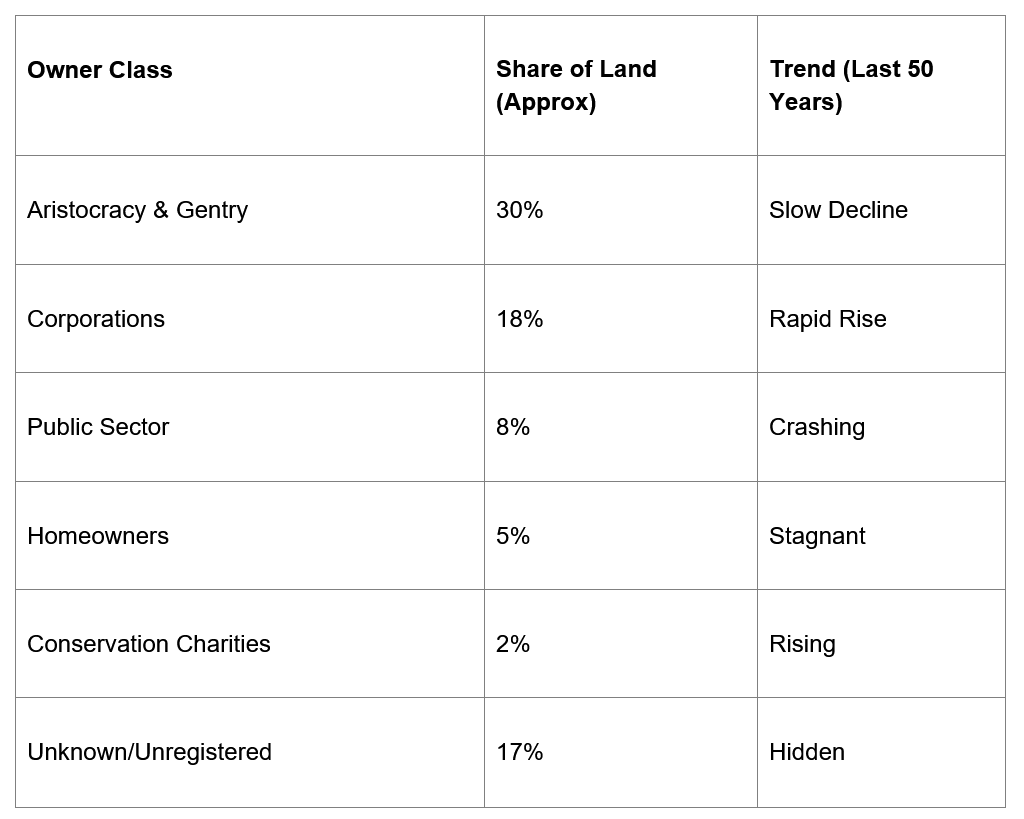

The UK’s land ownership patterns remain astonishingly concentrated, a situation exacerbated by decades of price inflation. The core statistic is stark: less than 1% of the population owns approximately 50% of the land. By contrast, the millions of homeowners in the country collectively own just 5% of the total land mass when their gardens and plots are summed.

Exponential price growth acts as a formidable barrier to entry, effectively “breaking the ladder” for new entrants. A young farmer cannot secure a loan to buy a farm when its price is based on tax shelter value rather than agricultural yield. A first-time buyer finds an ever-increasing portion of their income absorbed by the cost of the land under their home. This dynamic has also given rise to a new “Corporate Gentry”, as institutional investors like pension funds and insurance companies become major landowners, acquiring vast tracts of the country to secure natural capital assets and further concentrating ownership.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

6. Conclusion: A Market at a Crossroads

After fifty years of relentless price inflation, driven by a consistent and powerful combination of fiscal policy, credit expansion, and planning restrictions, the UK land market may be facing its first significant structural shift in a generation. The era of guaranteed, policy-driven capital appreciation is being challenged by new tax reforms, even as the “Green Rush” continues to reshape the valuation of the countryside. The market is at a crossroads, with competing forces creating both uncertainty and opportunity.

6.1 A Potential Policy Shock: The 2026 “Reeves Cap”

A major policy change is set to take effect from April 2026: the capping of 100% Agricultural Property Relief (APR) at £1million, now changed to £2.5million after a major campaign by those affected. For decades, this unlimited tax break has been a primary driver of farmland values, especially for large estates. The introduction of this cap is predicted to have two major effects. Firstly, it may trigger a “supply flush” as some owners of large estates sell land to bring their assets under the new tax-free threshold. Secondly, this could lead to a “market correction,” particularly for the large investment-grade properties that have benefited most from the tax shelter effect. This potential softening of prices may create the first significant window of opportunity for conservation buyers in over twenty years.

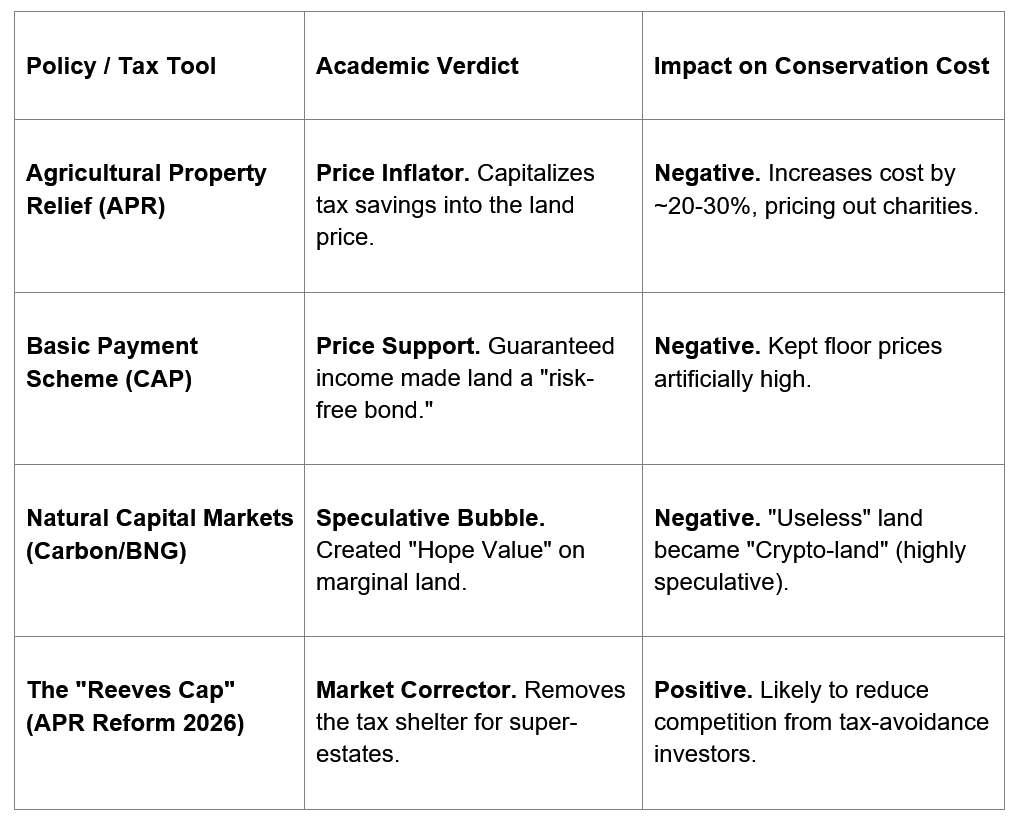

6.2 Summary of Policy Impacts on Price

This report has identified four key policy areas that have shaped land values. The following table provides a concise summary of their effects, based on the academic and market consensus.

Summary Table of Policy Impacts on Price

6.3 Final Synthesis

The fifty-year journey of UK land has been one of profound financialisation. It has transitioned from a productive commodity, valued for what it could grow, to a financial asset, valued for the tax it can shelter, the credit it can secure, and the environmental offsets it can generate. This report confirms the enduring relevance of Ricardo’s Law of Rent: as our economy has grown, the gains in wealth and productivity have not led to broadly shared prosperity but have instead been absorbed by rising land values, enriching a small class of landowners and widening societal inequality. The “Green Rush,” for all its environmental promise, risks becoming the latest and most potent driver of this trend, transforming the UK countryside into little more than a financial balance sheet for global capital. Without structural reform, the land will continue to act as a powerful engine of inequality, cementing a rentier economy where ownership, not effort, determines financial destiny.

7. The Solution

The historical analysis confirms that the UK economy has been distorted by the financialisation of land. An “invisible architecture” of tax breaks, credit expansion, and subsidies has transformed the countryside into a tax haven for the wealthy and a speculative balance sheet for global capital. This has resulted in the impoverishment of the working population (”mortal taxes”), the exclusion of conservation charities from the market, and the ecological degradation of the landscape (”Green Deserts”).

The Solution: A radical shift in taxation to capture Economic Rent—the unearned income derived from land ownership and natural monopolies—combined with strict Externality Pricing for environmental damage. This revenue will fund the total abolition of Income Tax and VAT.

7.1. The Core Mechanism: Annual Land Value Tax (LVT)

To dismantle the “Invisible Architecture” that inflates land prices.

Current fiscal policy (APR, CGT exemptions) subsidises land hoarding. I propose replacing these with a single Annual Land Value Tax (LVT) levied on the unimproved value of all land.

Impact on the Report’s Identified Drivers:

● Ending the “Tax Shelter” (Section 2.2): By levying an annual holding cost on high-value land, the LVT negates the benefit of Agricultural Property Relief (APR). Land will no longer be a tax-free vault for intergenerational wealth transfer. If the land is not generating productive yield to cover the tax, the owner will be forced to sell.

● Bursting the “Credit Bubble” (Section 2.1): As banks lend against the rental value of land, taxing away that rent reduces the capital value of the land. This breaks the feedback loop between mortgage credit creation and house prices. The “cost” of a home will return to the price of bricks and mortar, relieving poverty and vastly increasing the standard of living in the UK. It will also concentrate development creating more land area for nature to flourish.

● Capturing “Planning Gain” (Section 2.4): The report highlights that planning permission can raise land values from £10k to £4m per acre. Under LVT, as soon as land is rezoned for development, its taxable value rises accordingly. The community, not the landowner, captures the millions in uplift created by the state’s decision.

Outcome: The speculative premium on land collapses. Land prices fall to their use-value, resolving the “Conservation Purchasing Power Crisis” (Section 5.1) and allowing charities and new farmers to acquire land at affordable rates.

7.2 The “Green Tax” Shift: Pricing Negative Externalities

The Objective: To correct the “Green Rush” and “Efficacy Gap” (Sections 4 & 5.1).

The historical analysis confirms that the UK economy has been distorted by the financialisation of land. An “invisible architecture” of tax breaks, credit expansion, and subsidies has transformed the countryside into a tax haven for the wealthy and a speculative balance sheet for global capital. This has resulted in the impoverishment of the working population through “mortal taxes,” the exclusion of conservation charities from the market, and the ecological degradation of the landscape into “Green Deserts.”

The Proposal: A radical shift in taxation to capture Economic Rent—the unearned income derived from land ownership and natural monopolies—combined with strict Externality Pricing for environmental damage. This revenue will fund the total abolition of Income Tax and VAT.

7.1 The Core Mechanism: Annual Land Value Tax (LVT)

Objective: To dismantle the “Invisible Architecture” that inflates land prices.

Current fiscal policy (such as Agricultural Property Relief and Capital Gains Tax exemptions) effectively subsidises land hoarding. We propose replacing these with a single Annual Land Value Tax (LVT) levied on the unimproved value of all land.

Impact on the Report’s Identified Drivers:

● Ending the “Tax Shelter” (Section 2.2): By levying an annual holding cost on high-value land, the LVT negates the benefit of Agricultural Property Relief (APR). Land will no longer serve as a tax-free vault for intergenerational wealth transfer. If the land is not generating productive yield to cover the tax, the owner will be forced to sell, democratising ownership.

● Bursting the “Credit Bubble” (Section 2.1): Commercial banks lend against the rental value of land. Taxing away that rent reduces the capital value of the land. This breaks the feedback loop between mortgage credit creation and house prices.

○ Social Impact: The “cost” of a home will return to the physical price of bricks and mortar. This will relieve poverty by drastically reducing housing costs, which currently absorb a disproportionate amount of income for the poorest demographics, thereby vastly increasing the standard of living across the UK.

○ Environmental Impact: It will concentrate development in urban areas, creating denser, more efficient communities and leaving more land area for nature to flourish.

● Capturing “Planning Gain” (Section 2.4): The report highlights that planning permission can raise land values from £10,000 to £4 million per acre. Under LVT, as soon as land is rezoned for development, its taxable value rises accordingly. The community, not the landowner, captures the millions in uplift created by the state’s decision.

Outcome: The speculative premium on land collapses. Land prices fall to their use-value, resolving the “Conservation Purchasing Power Crisis” (Section 5.1) and allowing charities and new farmers to acquire land at affordable rates.

7.2 The “Green Tax” Shift: Pricing Negative Externalities

Objective: To correct the “Green Rush” and “Efficacy Gap” (Sections 4 & 5.1).

The report identifies a market failure where “Natural Capital” markets incentivise “Green Deserts”—monocultures that release soil carbon to capture tree carbon. A Georgist approach dictates that while the fruit of the land belongs to the worker, the integrity of the commons belongs to all. Therefore, damaging the commons must incur a cost.

Proposed Levies:

● The Soil Carbon Tax: Instead of subsidising tree planting, the state should tax the loss of soil carbon. If a landowner ploughs up carbon-rich pasture or dries out peatland to plant trees for credits, the tax on the released soil carbon would exceed the revenue from the forestry credits. This halts scientifically flawed “offsetting” projects immediately.

● Biodiversity Loss Levy: Landowners currently act as “free riders” when intensifying agriculture. A levy based on the reduction of biodiversity (measured against a natural baseline) forces the cost of ecological destruction back onto the balance sheet.

● Pollution & Nutrient Tax: A direct tax on nitrate and phosphate runoff. This removes the need for complex “Nutrient Neutrality” credit markets (Section 4.1) by making pollution economically unviable at the source.

Outcome: Conservation becomes the most economically rational use of land. The “Green Rush” speculators vanish because the “Hope Value” of degraded land is replaced by a tax liability for ecological damage.

7.3 The Great Tax Swap: Abolishing Income Tax and VAT

Objective: To end the “Nation of Rentiers” and relieve the poverty described in Section 5.

The report notes that the working population pays “mortal taxes” to subsidise the asset-rich. The Georgist solution demands the removal of all taxes that discourage production and exchange.

The Swap:

● Abolish Income Tax: The state stops penalising citizens for working. This immediately increases the take-home pay of the entire workforce, addressing the cost-of-living crisis at the source.

● Abolish VAT: The state stops penalising trade and consumption. This lowers the cost of goods and services, stimulating the productive economy.

Economic Logic: Currently, we tax what we want more of (work and trade) and subsidise what we want less of (land hoarding and pollution). By reversing this—taxing land monopoly and pollution while untaxing labour—we align economic incentives with social and ecological health.

7.4 Conclusion: From Financial Monopoly to Common Stewardship

Implementing this Georgist framework solves the specific crises identified in the report:

Inequality: The “Rentier” class (Section 5) can no longer live off the passive appreciation of assets. Wealth must be earned through production or stewardship.

Housing: The removal of land speculation lowers housing costs, while the removal of Income Tax raises wages. The gap between earnings and house prices closes.

Nature: The “Carbon Rocket” (Section 1) is grounded. Land values stabilise at productive levels. Conservation charities, no longer priced out by hedge funds, can acquire land to protect nature, while the tax system punishes those who create “Green Deserts.”

By capturing the economic rent created by the community and the planet, we return the value of the commons to the people, ensuring that land once again serves as a foundation for life, not a vehicle for financial extraction. Consequently, vastly more land will be available for nature, rewilding, and genuine carbon capture, directly addressing climate change by sequestering carbon back into the ground where it belongs.

Here is a curated list of references and further reading that underpins the economic and environmental arguments presented in your report. These sources cover UK land trends, Georgist economics, and the critique of natural capital markets.

References & further Reading

1. UK Land Values & The Housing Crisis

Harrison, F. (1983). The Power in the Land. Shepheard-Walwyn.

A seminal work predicting the 18-year property cycle and the 2008 crash, arguing that land speculation is the primary cause of boom-bust cycles.

Harrison, F. (2005). Boom Bust: House Prices, Banking and the Depression of 2010. Shepheard-Walwyn.

Further analysis of the “Ricardo Law” in action, demonstrating how the banking system fuels the land market.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) – UK National Balance Sheet Estimates

The primary data source showing the explosion in land wealth vs. productive assets.

Ryan-Collins, J., Lloyd, T., & Macfarlane, L. (2017). Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing. Zed Books.

Essential reading on how the banking system creates money to inflate land prices (The “Feedback Loop”).

Shrubsole, G. (2019). Who Owns England? How We Lost Our Green and Pleasant Land, and How to Take It Back. William Collins.

A deep dive into the 1% ownership statistic and the secrecy of land registry data.

2. Georgist Economics & Land Value Tax (LVT)

Gaffney, M., & Harrison, F. (1994). The Corruption of Economics. Shepheard-Walwyn.

Argues that neoclassical economics was deliberately engineered to hide the unique role of land, effectively protecting the “Invisible Architecture” of monopoly.

Gaffney, M. (2009). After the Crash: Designing a Depression-Free Economy. Wiley-Blackwell.

Explains how replacing taxes on labour and capital with taxes on land rent can prevent economic depressions.

George, H. (1879). Progress and Poverty.

The foundational text of Georgism, explaining why poverty accompanies economic growth due to land monopoly.

Smith, A. (1776). The Wealth of Nations (Book V, Chapter 2).

Adam Smith’s original argument that ground-rents are the most equitable subject of taxation.

3. Conservation, Rewilding & The “Green Rush”

Smith, P. Rewilding. Substack.

A dedicated platform analysing the intersection of land economics, rewilding, and the failure of current environmental markets. Critical reading for the “Green Deserts” concept and the economic argument for nature.

State of Nature Partnership. (2023). State of Nature Report.

The definitive guide to the decline of UK wildlife (16% of species threatened).

Monbiot, G. (2022). Regenesis: Feeding the World without Devouring the Planet. Penguin.

Chapters on soil ecology critically examine how agricultural intensity and “offsets” damage soil carbon.

4. Policy & Tax Reform Proposals

Fairer Share. (2020). Proportional Property Tax Campaign.

A modern campaign to replace Council Tax and Stamp Duty with a property tax (a step toward LVT).

Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). (2023). Taxing Wealth and Capital Income.

Analysis of Capital Gains Tax and Inheritance Tax loopholes (APR) mentioned in your report.

Land & Liberty Magazine (Henry George Foundation)

Ongoing commentary on UK land issues from a Georgist perspective.

Comments

Post a Comment